A Hospital based study on management of Health Hazards due to needle-stick injuries and its perception among healthcare professionals

Aishath Selna

Laboratory Director, Laboratory Science, ADK Hospital, Sosun Magu, Male’, Maldives

Sources of support:

In affiliation with Villa College QI Campus, RahDhebai Hingun, Male', 20373, Maldives

Additionally, approved by National Health Research Committee, Ministry of Health, Male, Maldives

ABSTRACT

Objective

To assess the perception regarding Health Hazards associated with Needle Sticks Injuries (NSIs) among Healthcare Professionals (HCPs) and, their views on how to minimise and manage exposure incidents in a Tertiary Care Hospital in Maldives.

Method

A qualitative research study done among the Heads of Departments (HODs) of Tertiary Care Hospital in Maldives who has HCPs working under them with great risk of exposure to hazards due to NSIs.

The research undertaken includes two sections, a quantitative and a qualitative section. The quantitative data section includes secondary data being obtained from the reported incidence records and stratified into groups of HCPs and displayed as a percentage in a bar chart.

The second section will use a methodology focused on qualitative analysis as the researcher wants to know in-depth information regarding the perception of HCPs, along with the knowledge on prevention and management of exposure incidents due to NSIs.

Result

The majority of the HODs had experienced a NSI in their work life. The non-compliance with the standard precautions, resource inadequacy as well as the lack of knowledge regarding risks, post exposure prophylaxis (PEP) and the reporting system for NSIs were major disquiets among HCPs.

Conclusion

The occurrences of NSIs were associated with organizational characteristics as well as behavioural characteristics and protective equipment. Hospitals can prevent or minimise such incidences by establishing standard protocols, creating awareness and educating and guiding the HCPs on safe handling of needles and proper disposal. Instigating proper monitoring system at organizational level and a reporting system at National level in Maldives is also vital.

Key words:- Needle stick injuries, Exposure incidents, Healthcare professionals, Vaccination, Hazards, Post Exposure Prophylaxis, Infection Control, Occupational Safety Health.

INTRODUCTION

Healthcare Professionals (HCPs) should not have to risk their lives every time they use a needle or sharp device. Even then they are exposed to different kinds of occupational hazards due to their day to day activities,because during patient care they use needles for diagnostic and therapeutic purposes. They are at high risk for job-related infection due to biological factors because these workers are frequently exposed to human body fluids. Each year, hundreds of thousands of HCPs face the risk for blood-borne diseases which are acquired in job situations due to Needle Stick Injuries. (NSIs). These injuries constitute a major threat to HCPs’ psychophysical well-being. Factors that can influence the risk of NSIs are equipment, design of instruments, working conditions and working practices (CDC, 2013). Working under demanding situations may result in fatigue, poor concentration, and carelessness, thus increasing the risk of NSIs. (Schmitz-Felten, 2013)

NSIs caused by sharp instruments such as hypodermic needles, blood collection needles intravenous cannula or needles used to connect parts of IV delivery system are common in clinical practice and have the potential risks of transmission of various fatal diseases such as, Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS) and Hepatitis, among others which are highly dangerous as it can have varied results ranging from transmitting life- threatening blood borne pathogens and many more known and unknown infections due to exposure. These infections could largely be prevented and mortality reduced by raising awareness, establishing methods to reduce exposures, immunization, making use of personal protective equipment (PPE), and post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) (Motaarefi, et al., 2016). At present there are limited universal or complete mechanisms of management of needle injuries implemented in the country or the institution, including data compilation with regard to NSI. It is important to find out how much, HCPs are aware of these risks and importance given by HCPs to minimise the exposure to such incidents and formulate strategies to improve them. Therefore, it’s a belief that safety is a must in the work place and the support of each staff is needed to achieve the task of “Healthy Staff –Healthy Patients”, which will help to reduce consequences that may arise due to exposure to hazards like NSIs.

Some HCPs also do not perceive NSIs to be a major threat to their daily work, or some do believe that NSIs are a part of daily healthcare procedures and need attention only when they do occur.

This study was conducted in a Tertiary Care Hospital, in Maldives. The importance of conducting this study was to get relevant information and to know the existing gaps regarding NSIs and how to minimize them. Moreover, to address this neglected area, limited research has been done and till date limited reliable source of information has been published or available in the Maldives, therefore this research is expected to highlight the primary issues surrounding NSIs and also the importance of their prevention and management.

Considering all these factors this study was conducted to find out perceptions, prevention methods and management of health hazards due to exposure to NSIs, as there has not been any research specifically done on this topic at the chosen setting in Maldives.

LITERATURE REVIEW

When a hypodermic syringe needle accidentally punctures or pierces skin at any time of use, or during disposing of it are known as NSIs. Most common occupational hazard that HCPs encounter are NSIs exposed in the work place with potential effects related to these injuries including the risk of transmission of blood borne pathogens such as HIV, HBV and HCV. ( Canadian Paediatric Society, 2008). Including these infections, there are also psychiatric morbidities that can arise after NSIs, such as depression, including post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and adjustment disorder (AD). (Bhardwaj, et al., 2014) The associated consequences to these effects include missed work days, which directly affect the healthcare services and resources. (Bhardwaj, et al., 2014).

A study done by Toraman et.al (2015) on an average, about 0.2% of all self-reported injuries are NSIs which is about one injury per month. Nurses sustained 36%, housekeeping staff 64%, Outpatient clinics 28%, Internal Diseases Inpatient Unit with 21% and the Medical waste room 14%. Another study shows that in-between 2000 to 2030, 16 000 HCV infections attributable to sharps injuries will result in 142 (51-749) early deaths. Similarly, the 66, 000 HBV infections will lead to 261 (86-923) early deaths, and about 736 (129-3578) HCPs will die prematurely from 1000 HIV infections (Pruss-Ustun, et al., 2003). During the recent years many studies have being published in an attempt to establish the risk to staff when exposed to infections through NSIs and mucocutaneous exposures. In reducing NSIs, occupational and patient safety programs are important interventions. (Toraman et al., 2015).

Globally, up to 3 million percutaneous exposures occur among HCPs of which 90% occur in the least developed countries resulting in upto 1000 HIV infections transmitted annually to HCPs. Occupational HIV infections in HCPs can be prevented by timely administering PEP, which can reduce the risk of HIV infection by up to 81% if properly used. (Mponela, et al., 2015). Due to their healthcare duties HCPs are frequently at risk for exposure to NSIs which constitute a major threat to HCPs psychophysical well-being. (Subramanian, et al., 2017).

The World Health Organization (WHO) global burden of disease data from sharps injuries showed that 37% of hepatitis B among health workers was the result of occupational exposure. Hepatitis B virus infection is 95% preventable with vaccination, but less than 20% of health workers in some parts of the world have received all three doses required for immunity. NSIs account for 95% of HIV occupational seroconversions, although upto 10% of HIV among health workers has been reported to occur from exposure at work. Risk of exposure to hepatitis, HIV, and blood-borne viruses and bacteria can be prevented with economic and practical measures (Subramanian, et al., 2017).

“SHARPS” are medical items used in health care, which have sharp points or cutting edges capable of causing injury to, or to pierce human skin during use. WHO describes sharps as scalp blades, broken glass, needles and any other sharp medical items that can contain infected blood and body fluids from the patients’ after use ( (Pruss-Ustun , et al., 2005). Types of needles include individual needles, syringe needles, lancets, auto injectors, infusion sets, and connection needles. (U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 2016).

HCPs use needles, syringes and other devices for collecting patients' blood and to inject drugs that are in liquid form (Reddy, et al., 2017).Such instruments can come in many forms. Hollow needles are used to inject drugs (medication) under the skin.Syringes are devices used to inject medication into or withdraw fluid from the bodylancets, also called “finger stick” devices or instruments with a short, two-edged blade used to get drops of blood for testing. Auto injectors, including epinephrine and insulin pens are syringes pre-filled with fluid medication designed to be self-injected into the body. Infusion sets are tubing systems with a needle used to deliver drugs to the body. Connection needles/sets are needles that connect to a tube used to transfer fluids in and out of the body. This is generally used for patients on home haemodialysis (U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 2016).

In industrialized countries, the first reported case of HIV infection caused by a NSI to a HCP caused tremendous concern and led to the implementation of efficient strategies to protect health-care workers. (WHO, 2003).

HCPs belief is that healthcare organizations’ need to ensure that they not only take the right measures to protect their employees from suffering an injury, but make sure the appropriate protocol is in place to support staff should such an incident occur. This should include, but is not exclusive to, simple and clear reporting procedures, psychological support and counselling, and timely test results. (Smiths Medicals, 2014).

Occupational NSIs are common among HCPs in a study done at a Swiss University Hospital. The low rates of underreporting could be explained by a number of beneficial factors such as better information at the time of engagement; continuous education throughout the time of employment; or perhaps more time allocated within their daily activities to facilitate reporting (Voide, et al., 2012).

The most important factor is to report if any incidental exposure occurs due to NSIs. Most of the HCPs are unaware of the hazards which may put them in real danger at work place especially in a hospital setting. Guidelines and policies need to be put in place and HCPs should be educated on the exposure hazards and the preventive precautions to be taken. Although the prevalence of BBPs in many developing countries is high, documentation of infections due to occupational exposure is limited. Seventy percent of the world’s HIV infected population lives in Sub-Saharan Africa, but only 4 % of cases are reported from this region. Under reporting of needle stick and/or sharps injuries in healthcare facilities was common (Bekele, et al., 2015).

Most of the HCPs believe that these infections can be life-changing and can have a great impact in one’s ability to fulfil their role as HCPs. However, even without the diagnosis of a serious disease, the emotional and psychological impact of NSI can be significant (Smiths Medicals, 2014).

It may not be possible to stop exposure incidents which are common in Health Sector, entirely, but can be minimized by following pre-set standard protocols. Even though all precautions are taken with PPE, these does not exclusively guarantee that the HCPs are not going to get exposed.

Although accidents are bound to happen, proper handling and precautions will play an important role in preventing these types of exposures. (Bhattarai, et al., 2014).

Needles are used by HCPs during diagnostic and therapeutic procedures. Ideally when using a syringe, the HCP or his assistant should not be located in the direction of the applied force. If the HCP is going to reuse the syringe, then the needle should be placed in a neutral zone and it should not be recapped unless the syringe is being put in a safety sheath. As a protective measure, safety syringes with spring-loaded or manually retractable needles that allow the needle to retract once the plunger is fully depressed can be used. (Rizk, et al., 2016).

Needle disposable techniques also play a vital role in NSIs prevention, including safety measures for the removal of needles form the work place after use. Raising awareness about the risks of exposure should be the first step for the HCPs to understand the reason for strict adherence with preventive measures, which include safe procedures for using and disposing of sharps, and banning of recapping of needles (Carli, et al., 2015).

Factors that can minimize NSIs include using PPE, educating HCPs for adopting best practices and health issues related to exposure incidents and also following guidelines and protocols on NSIs (Kumar, et al., 2015) . There are similar findings from Egypt, Lebanon and Delhi. The HCPs should be trained for correct PEP practices to follow after an exposure as well as motivated to complete vaccination program too. HCPs should be immunized for Hepatitis B vaccine which is the only vaccine available in order to protect themselves from BBIs. This vaccine has been available since 1982 and has a protective efficiency of 90% to 95%. HCPs exposed to NSIs, blood containing HBV, or both are at risk for developing clinical hepatitis. Various studies reported regarding incorrect practices has also highlighted the need for a coherent hospital policy regarding HCPs safety. (Kumar, et al., 2015).

According to a study done for HCPs in two Hospitals from Germany,there were500,000 NSIs occurring annually.It was also found that the awareness regarding management of exposure incidents for NSIs were very low. Out of 198 HCPs which were 70 doctors, 70 Nurses and 58 Laboratory technicians, only 101 knew the standard discarding methods of needles without recapping (Hofmann, et al., 2002). Also, 159 were still recapping, 180 were vaccinated against Hepatitis B, and only 36 were aware that blood should be allowed to flow and the site of the prick should be washed with an antiseptic after a NSI. (Qazi, et al., 2016). This shows the importance of educating the HCPs in managing if an exposure incident does occur.

HCPs in Hospitals and community settings should be informed and well educated about the occupational exposure risks and also should be aware of the importance of getting urgent advice following any NSI. Following an exposure incident, the first priority is to ascertain the HIV status of the patient, and from medical records if the status cannot be identified then with a consent from the patient, HIV testing should be done. Also in order not to delay the PEP, HIV results must be available within 8 hours and not more than 24 hours. PEP for HIV is recommended as soon as possible and not more than 72 hours after exposure to HIV. All recommended drugs should be available in the hospital setting. (Department of Health,UK, 2008). Among HCPs, NSIs are common and even in United States it is estimated that 600,000 to 800,000 NSIs occur per year. Of these many of the incidences goes unreported. (CDC, 1999)

The risk of acquiring HBV is related to the prevalence of HBV infection in the patient population with which the HCPs works. Patients who are HBsAg positive, either from acute or chronic infection, are potential sources of infection. Patients who are acutely infected may not be recognized since acute infection is symptomatic in only 10% of children and 30 to 50% of adults. Chronic HBV infection is often asymptomatic (Beltrami, et al., 2000).

High concentration of HBV may be present in the blood of carriers; the risk of clinical hepatitis B may be as high as 31% after a percutaneous exposure when the source patient is both hepatitis B surface antigen (HbsAg) and e-antigen positive. For HCV, the rate of percutaneous transmission is widely quoted as 1.8% (range 0 to 10%), but more recent data from larger surveys suggest that it is 0.5%.The overall rate of infection after an HIV-positive NSI is 0.3% (Berry, 2007)

Lack of knowledge about the correct procedures to be followed was prevalent, even the number of HCPs who followed best practices was low. Compared to the other categories of paramedics, Doctors had the better vaccination rate and the best PEP practices in place for a study done in a teaching hospital, Mangalore (Kumar, et al., 2015). Another research done stated that, for minimizing occupational risk of percutaneous and mucocutaneous exposure to blood and blood products the utmost importance should be given for education and training (Carli, et al., 2015).

METHOD

The research undertaken includes two sections, a quantitative and a qualitative section.

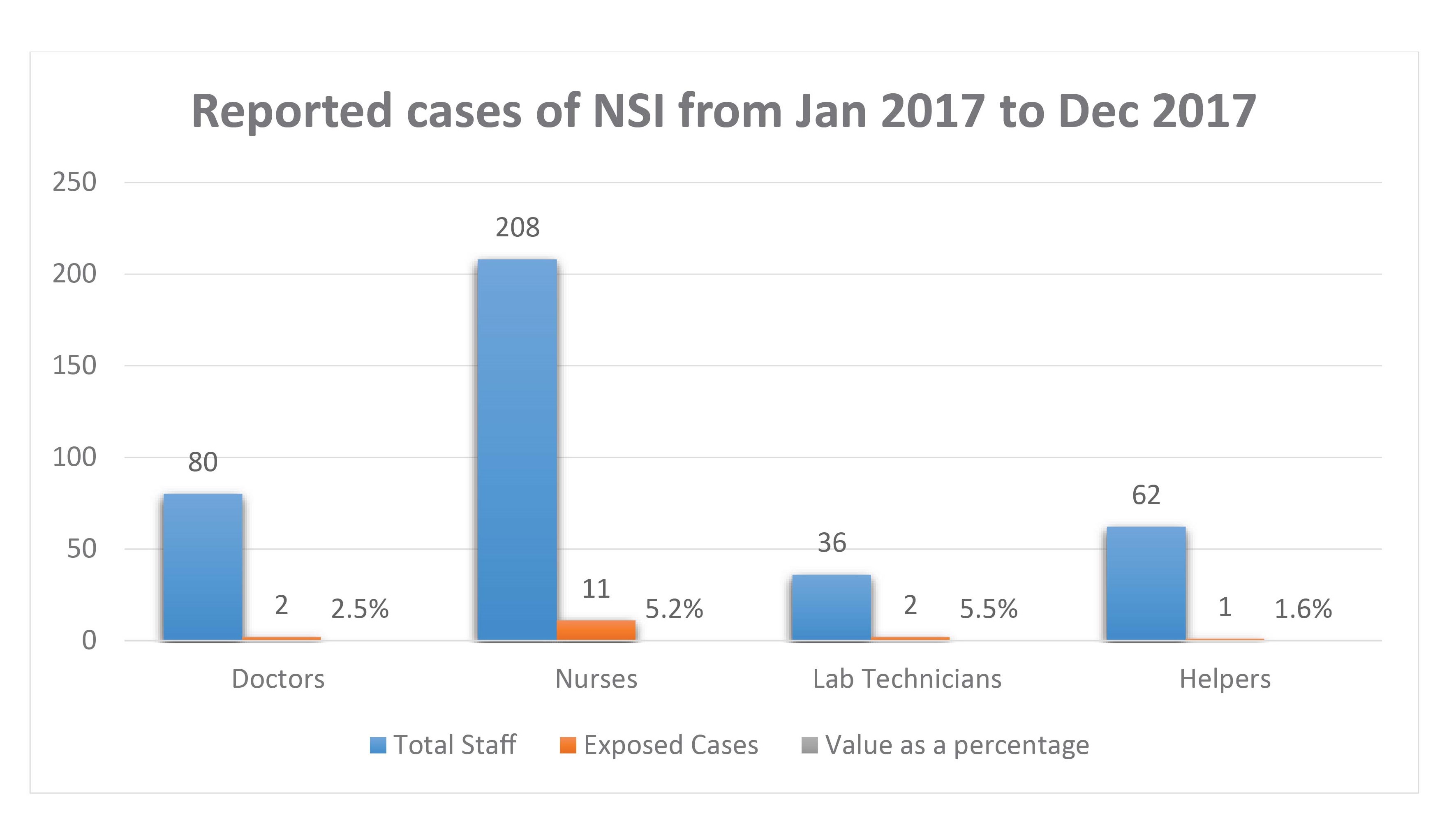

The quantitative data section includes secondary data being obtained from the reported incidence records and stratified into groups of HCPs and displayed as a percentage in a bar chart. The reported data was collected from Infection Control Committee (ICC) / Occupational Safety Health (OSH) records of the Tertiary Care Hospital in Maldives where the cases are currently reported, analysed and monitored.The incidences reported among all the HCPs are stratified into respective groups as Doctors, Nurses, Laboratory technicians and Helpers.

The qualitative research method was utilized to for obtaining in-depth information regarding the perception of HCPs, along with the knowledge on prevention and management of exposure incidents due to NSIs. A semi-structured questionnaire was used as the instrument and one on one interview were conducted to collect information. Analysis was done by doing a thematic analysis.

Sampling method was purposive sampling. Cases for interviews were taken from different categories of the medical and support services who are directly involved with patient care, where diagnostic or therapeutic uses of needles occur including disposal of such. Selected participants were interviewed based on a questionnaire conatining open ended questions. The interview guide was to probe into the practices adopted for the handling of NSIs, and the management of NSIs. Interviews were done on one on one basis for the HODs of departments of Tertiary Care Hospital in Maldives, having HCPs working under them who are directly involved in the collection, handling and disposal of needles contaminated with blood or body fluids, either for diagnostic or therapeutic purposes, and also questions regarding the reporting mechanism and the management of NSIs were included.Some of the selected participants were informed before the interview by meeting them and giving them the research invitation and the others by phone. When they gave a time and the place they want to meet for the interview, the participants were given the consent form and explained the purpose of the research study and also why they were chosen. Each participant was given a copy of the consent form. The interviews were recorded after getting approval from the respective participants. All the participants were willing to participate as in their opinion this is a very necessary step to be taken to find out the reasons for underreporting of NSIs in the Hospital.

The interviews were transcribed, after listening to the recorded interviews several times not to miss any important information and coding done on a word document. Main three themes were generated with six sub themes. All the participants had almost the same concern regarding the management of NSIs and the reporting process in the Tertiary Care Hospital.

RESULTS

Recorded data on reported cases for NSIs among the HCPs in Tertiary Care Hospital in Maldives

Table 1: Reported data for incidences of NSIs from January 2017 to December 2017

The data taken from the records are presented as a chart expressing the amount of incidences of NSIs recorded during the time of this study. The data is calculated as per the total number of incidences reported against the total number of staff from each stratified group of HCPs included in the study, which was then expressed as a percentage. According to the analysis, out of all the doctors 2.5% doctors had NSIs, out of all the Nurses 5.2% of Nurses had NSIs, out of all the laboratory technicians 5.5% laboratory technicians and out of all the helpers only 1.6% Helpers have been exposed to NSIs in the Year 2017.Total 16 incidences were reported from January 2017 to December 2017. Most of the cases reported were from Nurses. 11 incidences were reported from Nurses and two cases from Doctors and Laboratory Technicians respectively and only one case from the Helpers. An average of 14.8% incidences for NSIs was recorded in the year 2017.

The results from this qualitative research were specified in a textual description of the perceptions and experiences among the HCPs regarding the hazards due to exposure to NSIs. Four males and four females took part in the research project. Among the participants four were Doctors, two working in the Laboratory and two working in the clinical area. Three were Nurses and One from House Keeping. Five of the six HCPs (62.5%) who have handled needles in their profession have been exposed to NSIs in the past.All the participants had almost the same apprehension regarding the management of NSIs and the reporting process in the Tertiary Care Hospital.

Regarding perceptions most of the HCPs do know the major hazards associated with NSIs, such as HIV and Hepatitis, but their belief was that if vaccinated for Hepatitis B they are safe.

“I check fortunately for me patients screening was done. I have already taken hepatitis B vaccine.” (HCP-6)

Majority of the participants have encountered a NSI, while recapping or by accident due to unsafe methods of handling needles by their colleagues’ carelessness or resistance to change. All participants had concerns regarding their co-workers, describing that NSIs have occurred due to the carelessness or negligence of other professionals working with them, such as bare needles being put on the bedside of the patient without discarding it. The helper or the nurse who subsequently attends the patient has been exposed to this unattended needle, by sustaining a prick. One commented that HCPs do not take these things seriously and do not even report them. Two of the participants mentioned that if there was any incidence they do come to them and they do advice to inform to relevant personnel and follow protocols.

“Actually it was one day when I went to ER to visit a patient, some body was using that needle and it was on side of the bed which I didn’t notice and was attending to a patient and I poked myself. I didn’t see it and don’t know the source even”. (HCP-5)

“You do not give any sharp object hand to hand. But that [instruction] was shut down in the OT, I remember because of the reluctance of resistance on that, while saying that in other hospitals it is not done.” (HCP-7)

Minimising Hazards due to exposure of NSI’s is one of the major concerns raised by the participants. Even though they are aware of the universal precautions, most of them do not practice it.

“We do not follow universal precautions, we do not double glove, we do not use the goggles, and the gowns that we used are not water proof, so we use what is provided (for) us. ……I think it’s voluntary to use double gloves or not, because if you ask for two gloves you’ll get that, but I personally use one glove that is because it restricts my movements.” (HCP-7)

According to the HCPs, needle management methods including disposal and transport in Tertiary Care Hospital in Maldives need to improve and have to implement a complete process. While discarding proper measures are not taken and some of the HCPs are not aware of the proper process. One HCP mentioned that education and training in managing needles are an important concern among the HCPs.

The majority who responded stated that proper equipment like needle cutters, burners and destructors are needed at the work bench, while small sharp containers in trays to be used for cannulation. The transport of needles from one place to another may be a cause for NSIs unless proper precautions are taken. One staff had highlighted that needle discarding personnel sometimes do not take proper precautions such as even wearing gloves, therefore they need training and education. For needle disposal there need to the protocols put in place.

“Lots of NSIs occur while handling the waste also. ……So we have to look after both handling of needles and handling of waste also.so lots of education (is needed) in that area”. (HCP-3)

Majority of the participants were aware that there is a PEP process in the Hospital, but some were not aware of the implementation of the reporting system. Still education is needed in this area too.Some good advance techniques implemented at the hospital have really helped HCPs to perform their duties well, especially introducing vacutainers for phlebotomy of In-Patients (IP) and separate containers for disposal of needles which are puncture resistance.

“A reporting system established is not going to be effective if the HCPs are not aware how to make use of it when the need arises. The process need to be made practicable in such a way that the HCP will be encouraged to report the incidents”. (HCP-7)

“Right now we have a very good reporting system in which we have given special tasks of handling all NSI cases mainly by the ICN and OSH Nurse. So lots of staff right now are reporting these NSI cases”. (HCP-2)

“Right now so many staff are not aware…. so first thing is make sure they are aware of the reporting system”. (HCP-8)

Having a reporting system established is not going to be effective if the HCPs are not aware how to make use of it when the need arises. The majority have highlighted that they need to conduct workshops and trainings to make the HCPs aware on the importance of reporting a NSI. The process need to be made practicable in such a way that the HCP will be encouraged to report the incidents.

DISCUSSION

The records of the reported cases taken from a Tertiary Care Hospital in Maldives represents that 14.8% incidences for NSIs were recorded in the year 2017. As one participant has highlighted due to the difficulties in the process of reporting, many incidences would have been under reported. This may not be the true value of exposure incidences which may have occurred. Voide et.al (2012) claims that these low rates of underreporting could be explained by a number of factors: better information at the time of engagement; continuous education throughout the time of employment; perhaps more time allocated within their daily activities to facilitate reporting (Voide, et al., 2012).

The most important factor is that through a HCP the blood borne pathogens can be transmitted to the general public and vice versa. This study has explained these issues within the health care environment of a NSIs is a very common issue among HCPs, in this study which has been done most of the participants have handled needles in their work. One of the main focus of the research was to determine the perceptions. Even though the HCPs have experienced exposure to NSIs they are not aware of some of the consequences they may have to face after the exposure of NSI such as absence at work with may affect their patients in getting patient care. And also how it may affect their life and their families. Whilst majority of the HODs have been exposed to NSIs, and they are aware of the risks which may occur. A study done in 2003 stated that there were 3 million percutaneous exposures to blood-borne pathogens (BBP) among health care professionals worldwide (Pruss-Ustun, et al., 2003). These were caused by contaminated sharps, such as syringe needles, scalpels, and broken glass. This report, published in the “WHO Environmental Burden of Disease Series, No. 3”, also has highlighted that about 40% of all hepatitis B and hepatitis C cases present in HCPs were due to NSIs (Subramanian, et al., 2017). Most of the exposure incidents were due to carelessness, negligence of the workforce or recapping which is not recommended. And these incidences had led to exposure incidents with or without the role of the person managing the needle. It has had a great impact on some of the HCPs, like feeling guilty about the incidence, and taking the blame on themselves. Even though they know the fault is of the assisting HCP. Thus, having the knowledge that recapping is not a good practice still some of the HCPs do practice it, out of habit. It was also noted that some of the HCPs take these incidences very lightly and are not concerned about getting an exposure to a NSI. Their perceptions include a false sense of security, considering that if they are vaccinated then they are safe. HCPs need to know that there are a group of people called” Non responders”. Hepatitis B vaccine “non-responders" refers to a person who does not develop protective surface antibodies after completing two full series of the hepatitis B vaccine. An estimated 5-15% of persons may not respond due to other factors like obesity or chronic illness (Hepatitis B Foundation, 2017). These beliefs need to be addressed very closely as the consequences are vital to the Organizations, not only with financial burden of managing the NSIs but this can be burden for nations across the world. However, the most important is the emotional and psychological effect NSIs can have on the HCPs (Smiths Medicals, 2014). Not much research studies are available on perception of HCPs about NSIs. In a Hospital environment where, one person alone may not be able to work on bringing out a positive outcome, as it’s allabout team work. Every individual is responsible for oneself and also their subordinates’ and patients wellbeing. HCPs have a responsibility of their own to gain knowledge for themselves and educate other HCPs regarding minimizing and management of exposure incidents.

Minimizing exposure incidences to NSIs refers to the process of handling and disposing of needles in the proper manner. With regard to the knowledge based on the participants they all know the importance of using universal precautions. A series of effective precautions designed to protect HCPs from infection with a range of pathogens of blood and body fluids are known as universal precautions (Bekele, et al., 2015). However, some HODs as well as HCPs working under them do not perform accordingly. One HCP emphasized that using universal precautions is not a barrier to protect HCPs from NSIs. Whilst another stated that during crisis and emergencies have to attend the patient without Universal precautions. This negligence may have a great impact to the patient’s life as well as the HCPs, as the risk of getting exposed to blood borne pathogens are high, and the cause may not only be through an exposure incidence to NSI. Reilly (2010) states that Gloves offer virtually no protection against NSI but non sterile gloves should none the less be worn. The principal purpose of wearing gloves is to protect from cross-infection arising from local bleeding after the injection. Whilst another researcher states that perceived barriers to compliance with Universal precautions clearly influence HCPs ability and willingness to comply with them in practice. Inability to use PPE during emergencies, overwork and busy schedules have also been identified as major causes for exposure incidents (Kotwal & Taneja, 2010).

One obvious concern from all participants were needle management including the needle discarding methods. As a Tertiary Care Hospital the process for needle discarding methods need to be improved. Right now the needles are discarded to puncture proof sharp containers but most of the HCPs do not maintain the standard of filling it to 3/4th of the box. This leads to risks of being exposed to NSIs. To ensure safe disposal of needles, preventive measures must be taken but rarely its practiced among the HCPs. The consequences of not adhering to these will result in putting the HCPs in danger of exposing themselves to NSIs. Raising awareness among HCPs about the risks possibly deriving from their everyday activity is the first step to ensure they understand the reason for a strict adherence with preventive behaviours, which include safe procedures for using and disposing of sharps, and banning of recapping (De Carli, et al., 2014). Literatures revealed that there are many factors that contribute to NSI among HCPs. Such factors are irregular utilization of protective gear, type of occupation of HCPs, disposing of used needle, injecting medicine, recapping of needles and drawing of blood. Moreover, HCPs who followed universal precautions were 66% less likely to have NSIs than those who did not adhere to these recommendations (Bekele, et al., 2015). Moving needles from one place to another is also a known cause for NSIs unless proper methods are used. As one HCP responded that after cannulisation they have to take it out from the patient bedside to discard the cannula elsewhere, which implies that other people in the environment may have the affinity to get a prick. It may not always be a HCP, but can be another patient or a bystander. Denny (2014) claims that after performing procedures involving sharps, many wards in Hospitals have no quick and accessible 'point of care' sharps bin for their safe disposal. Instead one must transport potentially hazardous equipment away from the bedside, risking injury and exposure to HCPs and also patients (Denny, 2014).

The increase in the population of medical care seekers can have a great influence on the HCPs, contributing to the increase in use of sharps and sharp wastes. Innovative ways need to be introduced to overcome these challenges faced by the HCPs like blood transfer from syringes into tubes represent an example of an unnecessary use of needles in the laboratory setting which could be eliminated. The introducing of vacutainer needles for the in- patients for phlebotomy is one of the measures taken by the Hospital to minimize exposure incidents due to NSIs. Providing safety devices and mechanisms for needle disposal is best applied to minimize incidents. One participant did highlight that high technology needle devices like cannulas to be introduced in to the working system. Perry and Metules (2004) stated that when you have to use a needle, select those that have a safety device that's truly passive. By that we mean the safety device automatically activates after use. Another study done also states similar settings for effective needle stick injury prevention measures which include administrative and work practice controls such as educating workers about hazards, implementing universal precautions, eliminating needle recapping, and providing sharps containers for easy access that are within sight and arm’s reach (Wilnurn, 2014). Thus, this study even implies on the facts to bring out interventions and innovations to the practices applied in the Tertiary Care Hospital in order to minimize and manage exposure incidents due to NSIs.Due to lack of knowledge on the reporting system and the importance of PEP, most of the HCPs, even though they sustain a NSI they do not report. Even in this study setting it is more about lack of knowledge on the reporting system in the Hospital which inhibits the reporting of NSIs. A troubling concern identified in the medical literature is the failure of HCPs to report NSIs. A study done explains that, it is concerning due to the fact that a significant percentage of individuals infected with HBV or HCV are asymptomatic and unaware of their infection. The lack of reporting not only puts the HCPs at risk of contracting a blood-borne disease (BBD), but also puts the patients at risk if the HCPs does contract a BBD (Rizk, et al., 2016).

Most of the NSIs go under reported. It is estimated that nearly half of all NSIs go unreported. Yet the CDC insists on policies that support blame-free reporting, and the law requires confidentiality in reporting, which should help eliminate your fears about coming forward (Perry & Metules, 2004). Even though all recommended precautions are taken, there will still be incidences where NSIs may occur, but with the help of proper guidelines, immediate correct measure with help minimize them and save lives. This can be attained by educating yourself and your subordinates about risks associated with an exposure to NSI, getting to know more about PEP, being attentive to the policies and protocols established and the most important thing reporting the incidence and letting others take care of you.

CONCLUSION

The study was carried out by interviewing the selected participants who are Health care professionals (HCPs) working as HODs in departments of Tertiary Care Hospital in Maldives and has HCPs working under them with great risk of exposure to hazards due to NSIs. The aim of the study was to find the incidence rates, and knowledge they have in guiding the staff about prevention and management if exposed to NSIs.

Data gathered in the study was analysed by applying thematic approach. The interviews taken were transcribed and coding done to derive the themes. The themes were identified and subthemes included. The main findings were lack of knowledge regarding the hazards due to the exposure to NSIs and the reporting system established. Furthermore, the unsafe practice of using sharps like recapping, moving needles from one place to another after patient care and not using the proper techniques like using needle holders during surgeries. In addition, effective handling of needles and the management of needle appears to be a major public health issue. The untreated needles even though its advised to fill the sharp discarding containers to 3/4th of the box, it is not practiced So there is a high chance of getting a NSI to the people who manage the waste once it is expelled from the Hospital. Therefore, detailed information need to be shared and also proper equipment for needle waste management need to be put in place with protocols and policies for everyday practices and for the future. Even though a National policy for NSI is there, implementation of it is not in progress. Health care institutes need to be made aware and also a National reporting system must be established with network links throughout all the healthcare Institutes of Maldives for further management and monitoring of the NSIs.

Necessary precautions need to be taken to educate the HCPs at all levels to minimize and manage the risks and PEP if any exposure to a NSI occur. The implementation of the reporting system and the PEP process for NSI in the Tertiary Care Hospital had a great impact to some of the HODs who were aware of it. Like easy access to the reporting system and the identified person who will do the follow up and the monitoring. As previously it was a struggle to the HCPs to find out whom to report and what to do. These obstacles made them hinder the incidence and not approach anyone. However, awareness on the importance of reporting and using proper PEP for HCPs was not delivered due to the lack of awareness among some departments in the Hospital. The data collected for the NSI incidence rate itself explains that more nurses are aware of the reporting system as 11 cases were there and Doctors and Technicians it was only two cases; this doesn’t mean that it will be the true incident rate. And also only one incidence from helpers. More awareness among other departments need to be carried out with proper education, training and guidance.

The purpose of conducting this study was to create awareness among the HCPs to prevent and manage exposure hazards to NSIs for the wellbeing of themselves, their families and also the community.

Disclosure: I hereby declare that there is no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

1. Afiridi , A. A., Kumar, A. & Sayani, R., 2013. Needle Stick Injuries-Risk and Preventive Factors:A study among Health Care Workersin Tertiaty Care Hospitals in Pakistan. Global Journal of Health Science, 5(4), pp. 85-92.

2. Amira, C. & Awobusuyi, J., 2014. Needle-Stick Injury among Health Care Workers in Hemodialysis Units in Nigeria: A Multi-Center Study. THe international journal of occupation and environment Medicine, 5(1), p. 0.

3. Ballout, R. A. et al., 2016. Use of safety-engineered devices by healthcare workers for intravenous and/or phlebotomy procedures in healthcare settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Bio Med Central, Volume 16, p. 458.

4. Bekele, T., Gebremariam, A., Kaso, M. & Ahmed, K., 2015. Attitude,reporting behaviour and management practice of occupational needle stick and sharp injuries among hospital health care workers in Bale Zone,Southeast Ethiopia:a cross-sectional study. Biomed Central, 10(0), p. 42.

5. Beltrami, E., Williams, I., Shapiro, C. & Chamberland, M., 2000. Risk and Management of Blood-Borne Infections in Health Care Workers. Clinical Microbiology Reviews, 13(3), pp. 385-407.

6. Berry, A., 2007. Decision Making in Anesthesiology (Fourth Edition). Science Direct , 1(0), pp. 616-620.

7. Bhardwaj, A. et al., 2014. The Prevalence of Accidental Needle Stick Injury and their Reporting among Healthcare Workers in Orthopaedic Wards in General Hospital Melaka,Malaysia. Malaysian Orthopaedic Journal, 8(2), pp. 6-13.

8. Bhattarai, S. et al., 2014. Hepatitis B vaccination status and Needlestick and Sharps related Injuries among medical schoolstudents in Nepal: a cross-sectional study. Bio Med Central, Volume 7, p. 774.

9. Brown, D., 2008. Safety in Clinical Setting. ScienceDirect, 1(0), pp. 111-119.

10. Canadian Paediatric Society, 2008. Needle Stick Injuries. Paediatr Child Health, 13(3), p. 211

11. Carli, G. D., Abiteboul, D. & Puro, V., 2015. The importance of implementing safe sharps practices in the laboratory setting in Europe. Biochemia Medica, 24(1), pp. 45-56.

12. CDC, 2013. Stop Stick Campaign, Atlanta: NAtional Institute of Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

13. Creswell, J., 2012. Educational Research:Planning ,conducting and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research. 4 ed. Boston: Pearson Education, Inc.,

14. De Carli, G., Abiteboul, D. & Puro, V., 2014. The importance of implementing safe sharps practices in the laboratory setting in Europe. Biochem Med, 24(1), pp. 45-56.

15. Denny, J., 2014. Reducing Needle stick injuries in hospital. National Library of Medicine, 2(2), pp. 586-511.

16. Denzin, N. & Lincoln, Y., 2000. Hand book of Qualitative Research. 2 ed. Thousand Oaks: s.n.

17. Department of Health,UK, 2008. Guidance from the UK Chief Medical Officers’ Expert Advisory Group on AIDS, London: Department of Health.

18. Frickman, H. et al., 2016. Risk Reduction of Needle Stick Injuries Due to Continuous Shift from Unsafe to Safe Instruments at a German University Hospital.. Eur JMicrobiol Immunol, 23,6(3), pp. 227-237.

19. Gerberding , J. L., 1994. Incidence and prevalence of human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, and cytomegalovirus among health care personnel at risk for blood exposure: final report from a longitudinal study.. J infect Dis, 170(6), pp. 1410-7.

20. Goel, V., Kumar, D., Lingaiah, R. & Singh, S., 2017. Occurrence of needlestick and injuries among health-care workers of a tertiary care teaching hospital in North India. Journal of Laboratory Physicians, 9(1), pp. 20-25.

21. Hepatitis B Foundation, 2017. Health Awards. [Online]

Available at: http://www.hepb.org/about-us/mission-and-history/

[Accessed 20 12 2017].

22. Hofmann, F., Kralj, N. & Beie, M., 2002. Needle Stick injuries in health care-Frequency, causes and Preventive stretegies. Pubmed, 64(5), pp. 259-266.

23. Johnson, B., Dunlap, E. & Benoit, E., 2010. Structured Qualitative Research: Organizing “Mountains of Words” for Data Analysis, both Qualitative and Quantitative. HHS Public Access, 45(5), pp. 648-670.

24. Kothari , C., 2004. Research Methodology: Methods and Techniques. 2 ed. Jaipur: New age Internaitional.

25. Kotwal, A. & Taneja, D., 2010. Health Care Workers and Universal Precautions: Perceptions and Determinants of Non-compliance. Indian Journal of Community Medicine, 35(4), pp. 526-528.

26. Kumar, H. et al., 2015. A Cross-sectional Study on Hepatitis B Vaccination Status and Post-exposure Prophylaxis Practices Among Health Care Workers in Teaching Hospitals of Mangalore. Annals of Global Health, 81(5), pp. 664-668.

27. Maldives Health Master Plan 2016-2025, 2014. “For Our Nation’s Health”, Republic Of Maldives: Ministry Of Health.

28.Ministry of Health, 2017. Male': Not Published, Data obtained from MOH mail..

29. Morrison, M., 2017. Rapid Bi. [Online]

Available at: https://rapidbi.com/kurt-lewin-three-step-change-theory/

[Accessed 18 12 2017].

30. Motaarefi, H., Mahmoudi, H., mohammadi, E. & Hasanpour-Dehkordi, A., 2016. Factors Associated with Needlestick Injuries in Health Care Occupations: A Systematic Review.. PubMed, 10(8), pp. IE01-IE04.

31. Mponela, M. J., Oleribe, O. O., Abade, A. & kwesigabo, G., 2015. Post exposure prophylaxis following occupational exposure to HIV: a survey of health care workers in Mbeya, Tanzania, 2009-2010. The Pan African Medical Journal, Volume 21, p. 32.

32. National Bureau of Statistics, 2014. Population and Housing Census,Maldives, Republic of Maldives: National Bureau of Statistics.

33. National Bureau of Statistics, 2016. Ministry of Finance and Treasury. [Online]

Available at: http://www.planning.gov.mv/

[Accessed 18 12 2017].

34. Perry, J. & Metules, T., 2004. How to avoid needlesticks, Virginia: Medern Medicine Network .

35. Pruss-Ustun , A., Rapiti, E. & Hutin, Y., 2005. Estimation of the globalburdenof disease attributableto contaminated. Ameican Jounal of Industrial Medicine , 48(6), pp. 482-490.

36. Pruss-Ustun, A., Ripiti, E. & Hutin, Y., 2003. Global burden of disease from sharps injuries, Geneva: Environmental Burden of Disease Series, No. 3.

37. Qazi, A. et al., 2016. Comparison of awareness about precautions for needle stick injuries: a survey among health care workers at a tertiary care center in Pakistan.. Patient Saf Surg, 10(1), p. 19.

38. Reddy, V., Lavoie, M., Verbeek, J. & Pahwa, M., 2017. Devices for preventing percutaneous exposure injuries caused by needles in health care personnel. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews , 1(11), p. 0.

39. Rizk, C., Monroe, H., Orengo, I. & Rosen , T., 2016. Needlestick and Sharps Injuries in Dermatologic Surgery: A Review of Preventative Techniques and Postexposure. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol, 9(10), pp. 41-49.

40. Schmitz-Felten, E., 2013. Prevention of sharp injuries. Osh Wiki networking knowledge.

41. Scully, C., 2014. Scullys medical problems in Dentistry. 1(1), pp. 713-729.

42. Sharma, R., Rasania, S., Varma, A. & Singh, S., 2010. Study of Prevalence and Response to Needle Stick Injuries among Health Care Workers in a Tertiary Care Hospital in Delhi, India. Indian Journal of Community Medicine , 35(1), pp. 74-77.

43. Sin, W. W., Lln, A. W., Chan, K. C. & Wong, K., 2016. Management of health care workers following occupational exposure to hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and human immunodeficiency virus. Hong Kong Med J, 22(5), pp. 472-477.

44. Smiths Medicals, 2014. The emotional impact of Needle Stick Injury , U.S: The global technology business Smiths Group plc.

45 .Sossai, D. et al., 2016. Efficacy of safety catheter devices in the prevention of occupational. Journal of Preventive Medicine and Hygiene, 57(2), pp. E110-E114.

46. Subramanian, G., Arip, M. & Subramanium, T. S., 2017. Knowledge and Risk Perceptions of Occupational Infections Among Health-care Workers in Malaysia. Safety and Health at work, 8(3), pp. 246-249.

47. Tokars, J. I. et al., 2015. Surveillance of HIV infection and zidovudine use among health care. Ann Intern Med, 118(12), pp. 913-9.

48. Toraman , A. R., Battal, F., Ozturk, K. & Akcin, B., 2015. Sharps Injury Prevention for Hospital Workers. International Journal of Occupational Safety and Ergenomics, 17(4), pp. 455-461.

49. U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 2016. Safely Using Sharps (Needles and Syringes) at Home, at Work and on Travel, United States of America: s.n.

50. Voide, C. et al., 2012. Underreporting of needlestick and sharps injuries among healthcare workers in a Swiss University Hospital. 142(0).

51. Wang , S. et al., 2014. Incidence of ambulatory care visits after needlestick and sharps injuries among healthcare workers in Taiwan: A nationwide population-based study. Tha Kaohsiung Journal of Medical Sciences, 30(9), pp. 477-483.

52. WHO, 2003. Global burden of disease from sharps injuries, Geneva: Environment burden of disease.

53. WHO, 2017. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal. [Online]

Available at: Figure 5. Source: Causes of needle stick injury among the study population, Nigeria (Amira & Awobusuyi, 2014)

54. Wilnurn, S., 2014. Needle stick and Sharps Injury Prevention. The online journal of Issues in Nursing, 9(3), p. 0.