Minimizing Sample Rejection in a clinical laboratory: a pathway for quality care and safety of patients in a Tertiary Care Hospital, Maldives

Aishath Selna1, Adam Khaleel Yoosuf 2

Abstract

Aim

This study was conducted to evaluate the frequency, causes and result of pre-analytical errors encountered in a clinical laboratory.

Material and Methods

A retrospective study was conducted by collecting and analysing data of blood samples within the duration of two years (August 2016 to August 2018) from the laboratory.

Result and Discussion

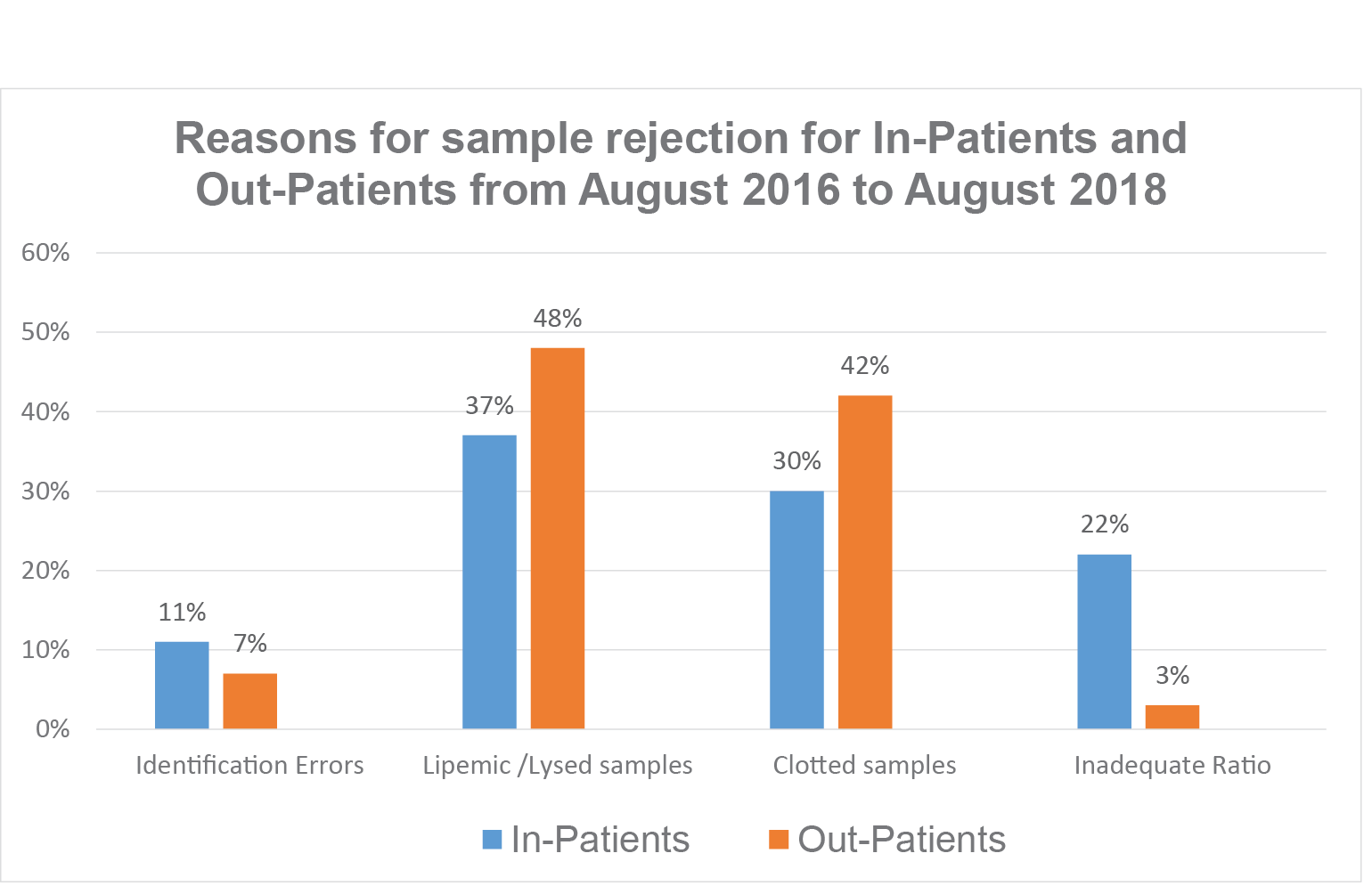

A total of 294,351 In-patients and out- patients’ samples were received in the laboratory during this period, with a total of 56,745 IPD samples, out of which in 0.33% samples, pre-analytical errors were found, which approximately constituted IPD 0.32% and IPD 0.013 % of all samples.Highest numbers of samples were rejected due to lysed/lipemic samples, which were 37% from IPD and 48% from OPD. About 30% in IPD and 42% from OPD was rejected due to clots in samples. And 22% of samples received from IPD were of inadequate ratio and 3% from OPD.

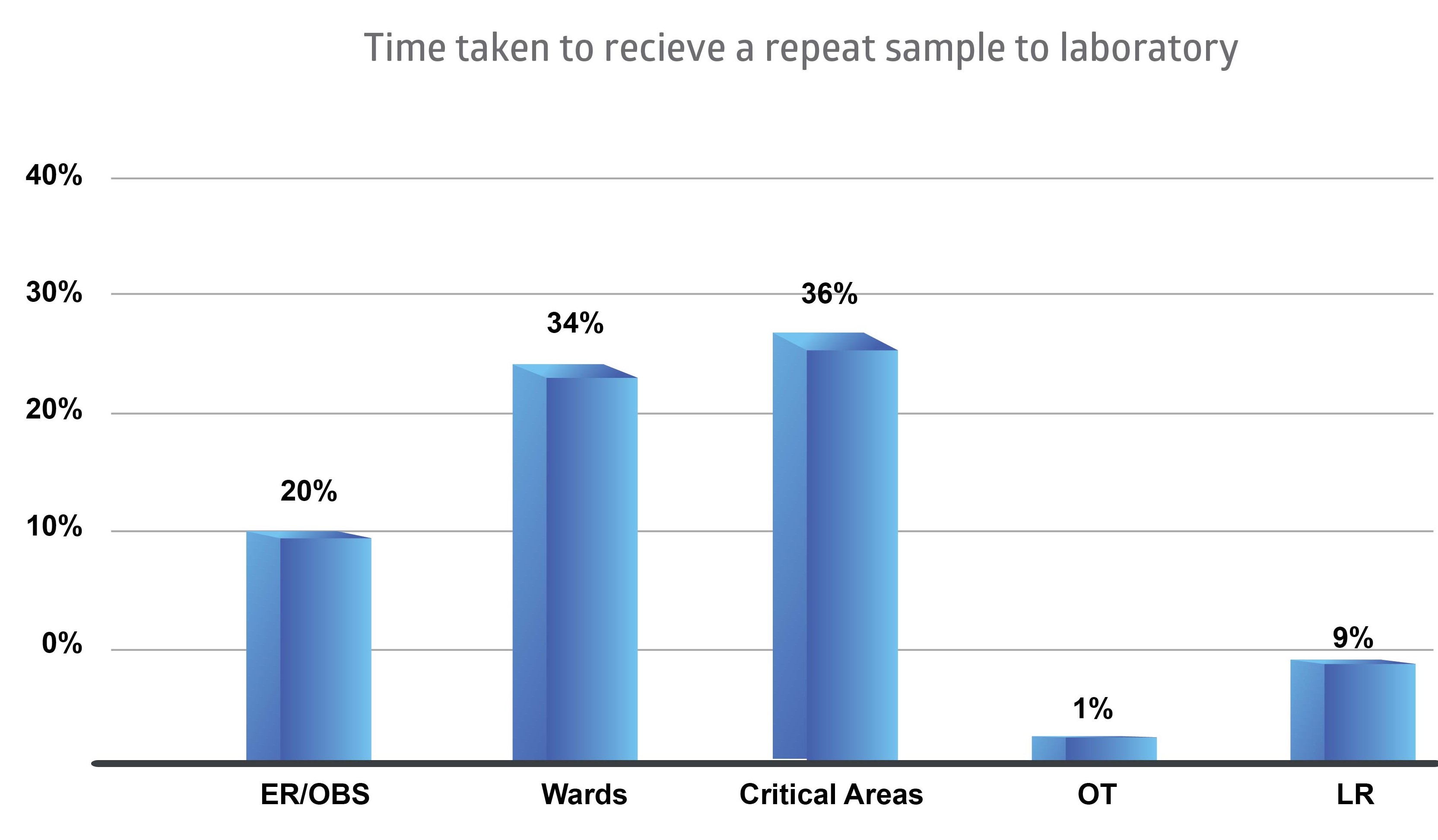

Highest percentage of samples were rejected from critical areas of the hospital (36%).

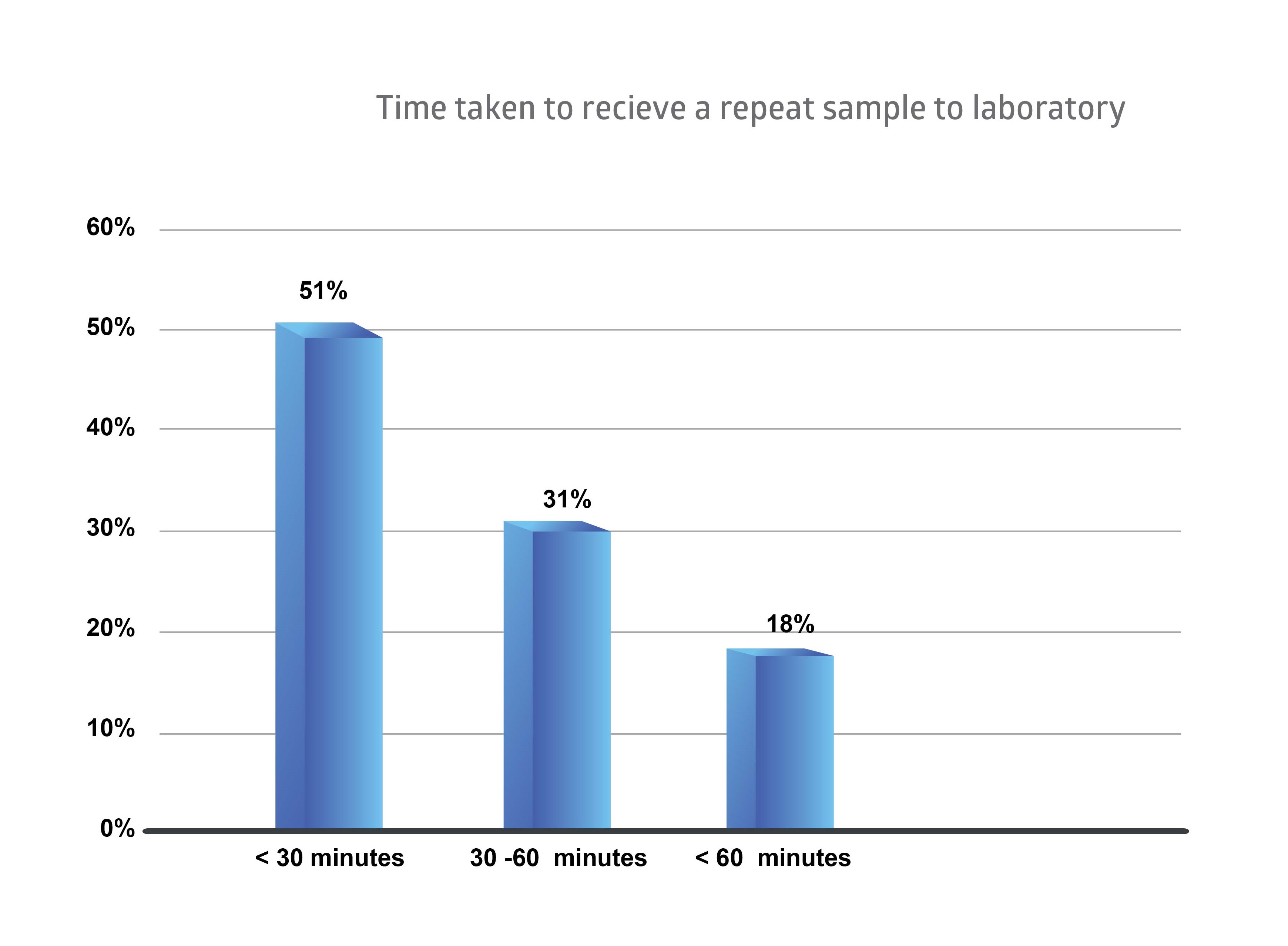

Turn Around Time for repeat sample was evaluated, 51% samples were received to the laboratory within 30 minutes of requesting for a repeat sample. But 31% of samples were received within one hour and 18% of the samples have exceeded one hour.

Conclusion

Importance has to be directed at reduction of all errors, with special consideration of pre analytical factors, for accurate and precise results for effective and safe patient care.

Keywords: Pre–analytical errors, Quality Management Systems, Clinical Laboratory, Sample rejection

Introduction

Clinical laboratories play a very crucial role in patient care and diagnosis through application of various laboratory testing methods, the results of which help clinicians make important decisions on patient care. There are a lot of variables involved in the process of laboratory testing which can ultimately influence the lab results issued (Chawla, Goswami, Tayal, & Mallika, 2010). For the results to be accurate and precise, laboratory reporting requires that all the phases involved i.e. pre-analytical, analytical and post–analytical, be free from errors, as much as possible (Hawkings, 2012). Many studies have been done to assess laboratory errors, and have reported that the largest numbers of errors are due to pre analytical factors, with estimates of up to 70 % errors noted in various studies (Jacobsz, Zemlin, Roos, & Erasmus, 2011).

The pre-analytical phase involves, among others, factors such as patient identification, sampling equipment, sampling methods, timing or special preparations, sample adequacy, sample quality, storage and transport (Shashi, Sanjay, Bansal, JeelaniN, & Bharat, 2013). In order to sustain the quality of pre-analytical variables, the laboratory needs to have Quality System Procedures (QSPs) implemented and followed within the laboratory, such as sample rejection criteria’s, sample numbering systems, billing system (if done at laboratory), labelling of urgent requests (this can be highlighted on the Test request form TRF), written policy on verbal requests, delivery of critical information (a placard, to display what consists of critical information, should be present in the reception area), storage of samples and handling of complaints apart from quality monitoring composed of records of incompletely filled forms, rejected samples, sample label errors and lost samples (Wadhwa, Rai, Thukral , & Chopra, 2012).

Many studies have been done in the past to find out sources of errors in laboratory testing and all agree that it is in the extra-analytical processes where the greatest number of errors occurs, especially in the pre-analytical phase. These processes are also the most critical and most difficult to manage, due to the decentralization of extractions and sample collection, involving the participation of various professionals such as physicians, specialists of laboratory medicine, nurses, laboratory technologists, and phlebotomists within different organizations and healthcare centres (Gimenez-Marin, Rivas-Ruiz, Perez-Hidalgo, & Monila-Mendoza, 2014).

After collection, the samples are tested in the analytical phase, and results reported in the post analytical phase, both of which also require quality standards. Errors occurring in the analytical phase can be due to, equipment malfunctions, sample mix-ups, interferences (endogenous and exogenous), and other undetected failures in quality control. Errors occurring in the post analytical phase can be due to failure in reporting/addressing the report, erroneous validation of analytical data, excessive turn-around-time, improper data entry and manual transcription error, failure/delay in reporting critical values, delayed/missed reaction to laboratory reporting, incorrect interpretation, inappropriate/.inadequate follow-up plan, failure to order appropriate consultation (Hawkings, 2012).

The aim of this study was to find out pre-analytical errors that have been recorded for the period of August 2016 to August 2018, in blood samples of IPD and OPD patients received in the laboratory. Data for all the pre-analytical factors according to predefined categories were identified so that corrective actions can be suggested, and implemented as part of quality improvement and patient safety.

Literature Review

In the advancing medical diagnostic scenario,around 60-70% of medical decisions related to diagnosis and treatment planning are dependent upon the medical laboratory services.This highlights the significance of testing to be done on correct sample (pre-analytical phase) with accurate and precise techniques (analytical phase) at the earliest (post-analytical). Even in the "World Health Organization-World Alliance for Patient Safety" states that impressive improvement has occurred in the analytical stage of laboratory medicine, but the pre-analytical and post-analytical phases are still vulnerable to errors (Gupta, et al., 2015).Another study done by Kaushik and Green, 2014 also states that a clinical laboratory plays an increasingly significant role in the patient-centered approach to the delivery of healthcare services. Physicians rely on accurate laboratory test results for proper disease diagnosis and for guiding therapy; it is estimated that more than 70% of clinical decisions are based on information derived from laboratory test results. The process of blood testing, also known as the “Total Testing Process,” begins and ends with the patient. It includes the entire process from ordering the test to interpretation of the test results by the clinician (Kaushik & Green , 2014) .Pre-analytical errors are the responsibilities of the blood collector and include the following:

- Monitoring of specimen ordering

- Correct patient identification

- Patient communication and safety

- Patient preparation

- Timing of collections

- Phlebotomy equipment

- Collection techniques

- Specimen labeling

- Specimen transportation to the laboratory

- Specimen processing (Dr.Goswami, Dr.Roy, & Dr.Goawami, 2014)

Since publication of a report entitled “To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System” by the Institute of Medicine there has been increased interest in issues involved with reducing patient errors and improving the quality of the reports generated which as a great impact on patient safety. Patient identification (ID) and accurate specimen labeling during phlebotomy procedures are crucial first steps in the prevention of medical errors. At least two patient identifiers should be used before collecting a specimen. All identifying labels must be attached to specimen containers (Ning, Lin, Chiu, Wen, & Peng, 2016). The role of clinical pathology and laboratory medicine continues to develop as the single largest component in day to day clinical practice as well as long term follow-up. The result of any laboratory examination becomes good enough only if appropriate samples are received in the laboratory (Dr.Goswami, Dr.Roy, & Dr.Goawami, 2014) . A study done by Jones et al (1997 reported that pre-analytical errors were about approximately 25% to 50% of the total errors in a clinical laboratory. National and international programs to track the quality of the laboratory have reported laboratory specimen rejection rates ranging from 0.3% in outpatient facilities to 0.83% in hospital based laboratories (Dr.Goswami, Dr.Roy, & Dr.Goawami, 2014).However, measuring and managing pre-analytical critical errors continues to be the major challenge facing clinical laboratories and the main difficulty lies in achieving an effective, systematic design to ensure the delivery of safety procedures and processes with necessary corrective actions. Many factors affect patient safety, as well as the sub –process, services and health care professionals involved in the pre-analytical phase. This is a complex phase and it is difficult to manage pre-analytical critical error, may be this is one reason why scientific literature in this respect provides very limited data, being focused more on estimating the frequency and specification of errors related to sample quality then the impact of quality care and safety of the patients (Gimenez-Marin, Rivas-Ruiz, Perez-Hidalgo, & Monila-Mendoza, 2014) . A study which included about beliefs of nursing staff stated about haemolysis (one of the major factors of sample rejection) that they believed that when a specimen is haemolysed, that haemolysis was dependant on the laboratory staff performing the analysis, and that anticoagulant therapy might cause haemolysis in the samples (Yeates, RL, 2016).

When the quality of a blood specimen is poor, it cannot be processed by the laboratory. This leads to a second request for blood specimen and therefore to an increased turnaround time for the laboratory, which is positively correlated with the delay in diagnosis. About 90% to 96% of the diagnostic delays have been attributed to problems associated with errors in pre-analytic phase of laboratory medicine. Patients' perception of quality of care is based on the timely access to and discharge from the health care facility, safety, efficient care coordination, and the number of specimens collected (Stark, et al., 2007). Pre-analytical errors damage an institution’s reputation, diminish confidence in healthcare services, and contribute to a significant increase in the total operating costs, both for the hospital and laboratory. Even though it is not possible to eliminate all pre-analytical errors, compliance with best practices can significantly reduce their incidence. Proper management of pre-analytical errors requires significant inter-departmental cooperation, since many sources of these errors fall outside the direct control of laboratory personnel. Laboratory professionals must be leaders in ensuring patient safety, both outside and inside the walls of the laboratory (Kaushik & Green , 2014).Errors at any of these stages can lead to a misdiagnosis and mismanagement and represent a serious hazard for patient health.The increasing attention paid to patient safety, and the awareness that the information provided by clinical laboratories impacts directly on the treatment received by patients, has made it a priority for clinical laboratories to reduce their error rates and promote an excellent level of quality service (Chhillar, Khurana, Agarwal, & Singh, 2011). Whilst another study states that given the high volumes of laboratory tests performed globally, even a low prevalence of errors translates into significant absolute numbers of occurrences and opportunities for adverse patient outcome (Hawkings, 2012). However, in a patient-centered approach to the delivery of health care services, there is the need to investigate any possible defect in the total testing process that may have a negative impact on the patient. In fact, in the interests of patients, any direct or indirect negative consequence related to a laboratory test must be considered, irrespective of which step is involved and whether the error is caused by a laboratory professional or any other health care professional.Patient misidentification and problems in communicating results, which affect the delivery of all diagnostic services, are widely recognized as the main goals for quality improvement (Plebani, 2009).Shortening turn-around-time (TAT) is one of the quality indicators in emergency laboratories. Improvement in TAT is related with correct pre pre-analytical phase procedure; receiving the appropriate sample from the right patient on time is necessary to achieve reliable laboratory results and promote patient safety (Dikmen, Pinar, & Akbiyik, 2015).

In a study done in UK to reduce pre-analytical errors from 2010-2011, two interventions were introduced. The first intervention involved raising awareness by displaying posters for 2 weeks after explaining to the ward staff about pre-analytical errors (insufficient sample volume, inappropriate tube selection). The second was about introducing of reminder screensavers, both these failed as no significant effect was on the frequency of these pre-analytical errors.” (Yeates, RL, 2016). Most errors are due to human factors. These may be reduced with the introduction of an electronic ordering system (Kemp, Bird, & Barth, 2012) . A custom label system minimizes the potential oversight of forgetting to draw a tube, which happens frequently when operating without appointments, by printing the labels according to requested tests. Detection, identification, and monitoring of the error and implementing strategies to improve pre-analytical quality reduces error numbers and thereby improves patient safety and health system outcomes (Lillo, et al., 2012) . The conclusion was that “time constrains and high workloads mean that human error will occur unless human input is eliminated by automation (Yeates, RL, 2016).

Methods

A retrospective study was conducted analysing rejection rate of routine and urgent blood samples received from OP, IP wards as well as from Emergency Department (ED) and Observation Ward (OW) at a clinical laboratory of a tertiary care hospital. In the Outpatient Department (OPD) the patients are attended by well-trained phlebotomists from the phlebotomy services unit within the Department of Laboratory Medicine. Inpatient phlebotomy services in the ED, OW and IP wards are provided by nurses.

All data entry was done manually and it’s recorded in a sample rejection register at the reception counter where all the samples from IPs and OPs are accepted. The quality of samples was assessed at the counter where samples are accepted or rejected. Furthermore, the samples which are accepted from the reception counter may be rejected after centrifugation of the samples (check for haemolysis and lipemia). For rejected samples whether a repeat sample was requested and the time taken for a repeat sample to reach the laboratory were analysedbecause turnaround time for the reports is crucial for the patient. The findings were reported as an average. All the patients’ blood samples received to the laboratory during the study period were included in this study. These data was analysed separately for IPs and OPs.

The data was collected over a period of 2 years (August 2016 to August 2018) and the impact of the rejected samples were assessed in several ways. The reasons for rejection was categorized in to four main components such as identification errors, clotted samples, lipemic and lysed samples and insufficient volume or inadequate ratio. The statistical data was analyzed and reported as a percentage value and displayed as a graph. The total number of blood samples received and the total number of IP and OP samples received to the laboratory were derived from the Hospital software. The samples were rejected according to the policy (implemented on 24th January 2015) of the clinical laboratory of the tertiary care hospital:

Acceptance:

All test requisitions and specimens delivered to that laboratory must meet the defined criteria for testing:

- Identification (Full name and Hospital Number)

- Proper labelling of specimen and requisition

- Collection criteria

- Transportation in accordance with the Transport of Dangerous Goods Regulations

Rejection:

Specimens unsuitable for testing include examples such as:

- Clotted samples except the serum tube samples

- Lipemic and Haemolysed samples (After centrifugation if haemolysis is noticed)

- Insufficient quantity and samples collected beyond mark of the blood collection tubes (inadequate ratio)

- The identification on the requisition and specimen do not match each other

- Unlabelled or mislabelled specimens

Additionally, the data collected was assessed to find out from which Inpatient department more samples were rejected and the findings was displayed in a graph.

Furthermore, the average time taken for a repeat sample to receive the laboratory was analysed.

(Samples which do not meet the required criteria for testing, are discarded without analysis and informed to respective departments for repeat sampling with proper technique)

Results

The available data were analysed to detect numbers of rejected samples due to pre-analytical errors as well as numbers of repeat samples and duration of receiving them, from different departments of the hospital.

A total number of 294,351 in-patients and out-patients’ samples were received in the laboratory during this period (August 2016 to August 2018), with a total of 56,745 IPD samples. The data analysed were categorized in two main categories OPD and IPD respectively and these data were analysed to detect number of rejected samples without analysis and also where repeat sampling were requested. From IPD frequency, origin and the time taken for a repeat sample to reach the laboratory was analysed and data displayed as percentages by graphs. From OPD only frequency was analysed. The total percentage of sample rejection from IPD was 0.32% and from OPD was 0.013%.

Reasons for Sample rejection for in-patients and out-patients

The rejected samples were categorized according quality indicators as follows:

- Identification errors

- clotted samples

- Lipemic / haemolysed samples

- Insufficient volume or inadequate ratio.

Figure 1Sample rejection data from IPD and OPD expressed as a percentage

The data shows that among the rejected samples most were rejected due to lysed/lipemic samples, from 37% from IPD and from 48% form OPD. About 30% in IPD and 42% from OPD was rejected due to clots in samples. And 22% of samples received from IPD were Inadequate Ratio (either the sample was taken less than the mark in the tube or the sample exceeded the mark) whilst 3% was rejected from OPD. Identification errors were 12% in IPD and 7% in OPD. (Identification errors for the purpose of inclusion were mismatch between the information on request form with specimen label.)

The Data of Sample rejected from Wards, ER /Observation Room, Critical areas, Labour Room and OT.

These are samples collected by nurses from in-patients.

Figure 2Sample rejection data as a percentage from Wards, Critical areas, LR, OT, ER and OBS.

Highest percentage of samples were rejected from critical areas of the hospital (36%). The critical areas are Intensive Care Unit (ICU), High Dependency Unit (HDU), Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) and Coronary Care Unit (CCU).

The remaining rejected samples were 34% from the wards, 20% from Emergency Room (ER) and Observation Ward (OBS), 9% from Labour Room (LR) and 1% from Operation Theatre (OT).

The Time taken for receiving a Repeat Sample after rejection

When samples are rejected due to pre-analytical errors, the respective in-patient departments are asked to send a repeat sample for analysis. The time taken for such samples to reach laboratory were recorded and is presented below.

Figure 3Time taken to receive a repeat sample to laboratory

The above graph shows that 51% samples were received to the laboratory within 30 minutes of requesting for a repeat sample. But 31% of samples were received within one hour and 18% of the samples have exceeded the one-hour time frame.

The sample quality and time are two important factors for quality patient care.

Discussion

The processes involved in laboratory testing include multiple phases which are, pre-analytical phase (mainly involving sampling before testing), analytical phase (mainly involving testing of the sample), and post-analytical phase (mainly involving the reporting of results). In order for risk management and patient safety it is necessary to prevent, detect and mitigate errors which occur during these phases. Various studies have demonstrated that most of the laboratory errors occur during the pre-analytical phase. (Shashi, Sanjay, Bansal, JeelaniN, & Bharat, 2013).

In this study done for a clinical laboratory for a Tertiary Hospital, reasons for sample rejection during the pre-analytical phase were assessed after categorizing them into four main components i.e.identification errors, clotted samples, lipemic and lysed samples, and samples of insufficient volume or inadequate ratio.

It was seen that from IPD and OPD, most of the rejected samples were due to lipemia and haemolysis (IPD 38% and OPD 48%).Reasons for specimen rejection may not be fully understood and reported that pre-analytical errors constituted between 25% and 50% of the total errors in the clinical laboratory with haemolysed specimens as the primary error (Stark, et al., 2007). After haemolysis, lipemia is the most frequent endogenous interference that can influence results of various laboratory methods by several mechanisms. The most common pre-analytical cause of lipemic samples is inadequate time of blood sampling after the meal or parenteral administration of synthetic lipid emulsions (Nikolac, 2014).Other reasons for rejection incudes clots in samples and in this study from IPD 30% and from OPD 42% of samples were rejected due to this factor.A study done in emergency laboratory in Hacettepe University Hospitals it has been noted that visible clots, either as a red cell clot in whole blood or a fibrin clot in plasma, are usually received from intensive care units, emergency department and new-born premature services. The major cause of clotted samples is probably due to poor mixing after blood collection and leaving the tubes horizontally instead of keeping them vertical. All diagnostic blood specimens collected in vacuum tubes are recommended to be inverted gently several times by all vacuum tubes manufacturers’ datasheets and Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) documents to maximize the contact between blood and additives following blood collection (Dikmen, Pinar, & Akbiyik, 2015).

Rest of the samples rejected due to identification errors and inadequacy of the sample. Identification errors from IPD was 11% and IPD was 7%. Some identification errors, such as incorrect demographic data do not usually reach lab, as they are corrected, before that, or completed at the time of phlebotomy. Laboratory request forms provide information about the laboratory tests being requested as well as certain demographic data and other details like ward, laboratory number, treating doctor’s names and signature and also clinical diagnosis. Omission of information on the forms may lead to laboratory errors (Sharaki, Abouzeid, Hossam, & Elsherif, 2014).

Inadequacy of the sample means inappropriate or low quantity or excessive quantity. From IPD inadequate samples sent were 22% but from OPD it was only 3% for the study done in the tertiary hospital. In a study done by (Dikmen et al, 2015) states that in sufficient samples are the second common reason (22%) for sample rejection due to the difficulty of collecting sufficient samples from new born, children, oncology and ICU patients.

Another area where data collected and analysed was to check the sites from where the samples were rejected. From the hospital most of the rejected samples were from critical areas such as ICUs. This may mostly be due to the processes involving sample collection. These are areas which require prompt reports for decision making in patient management and sample rejections can cause delays. It is common for the medical staff at the ED (Emergency Department) and inpatient services to collect a blood specimen through an intravenous catheter at the time of its insertion to minimize the patient's discomfort and to save clinical time. However, this practice has been reported to increase the likelihood of hemolysis because of flow through the narrow tube and the tendency of the conduit to tighten or even collapse in response to the negative partial pressure exerted by the suctioning pressure. In addition, the lesser proficiency and training of the nursing staff in phlebotomy relative to the trained laboratory phlebotomist may be another reason for the higher specimen rejections in ED and inpatient services (Stark, et al., 2007).

Rejected samples require repeat samples, which require time, efforts, resources, delays. One of our study aim was to find out the time taken for a repeat sample to reach laboratory for analysis. The results show that 51% samples do reach the laboratory within 30 minutes and 31% of the samples within one hour but 18% of samples takes more than one hour. The Turnaround Time (TAT) does have a great impact on patient care.Furthermore, timeliness which is expressed as the turnaround time (TAT) is often used by the clinicians as the benchmark for laboratory performance. Clinicians depend on fast TATs to achieve early diagnosis and treatment of their patients and to achieve early patient discharge from emergency departments or hospital in-patient services. Assessment and improvement of turnaround times is essential for laboratory quality management as well as ensuring patient satisfaction (Goswami, Singh, Chawla, Gupta, & Mallika, 2010) .For clinical management of patients sample rejection may have significant consequences.Patients whose specimens are rejected are frequently subjected to repeated specimen collection, resulting in inconvenience, the discomfort of repeated phlebotomy or other collection procedures, and/or the potential need for blood transfusion due to excessive iatrogenic blood loss.Specimen recollection ultimately lead to a delay in specimen analysis and the availability of test results.The prolonged turnaround time is clinically most significant for tests ordered with a stat testing priority, but similar delays may also impact routine and other non-stat tests (Karcher & Lehman, 2014)

Diagnostic investigations are the back bone of patient care as clinical decisions heavily rely on the performance and interpretation. The introduction of modern instruments in laboratory medicine has made investigations more perfect but it is crucial to be aware that there may be factors affecting results. Nursing staff, phlebotomist, junior doctors, consultants, laboratory staff and pathologist all must act in tandem as their collaborative team effort can ensure best patient care (Sareen & Dutt, 2018).

Repeat collection of samples, due to rejection of previous erroneous sample, results in expending more resources than actually needed. These are additional costs, and therefore methods need to be put in place to correct pre analytical errors to reduce such unnecessary costs. Blood sampling also involves various risks for the patient and staff including needle stick injuries/ sharps injuries or mucosal exposures, that can result in blood borne virus infections such as hepatitis or human immune deficiency viruses. Repeated sampling due to factors like sample rejection, can increase these risks for staff and patients also (Bekele, Gebremariam, Kaso, & Ahmed, 2015).

All data entry for this study was done manually as per the current existing laboratory system and it’s recorded in a sample rejection register at the reception counter where all the samples from IPs and OPs are accepted. For correct and accurate data entry and retrieval, laboratory integration, as well as a proper data retrieval system is needed. For each sample there should be a way to record all laboratory process factors. Some pre analytical errors, although not included in this study, are noticed only after samples have been analysed, or at the time of result entering, such as diluted samples. These are additional factors which cause loss of time and resources, apart from the mentioned sample rejections.

The management of quality in pre-analytical laboratory practices is a challenging enterprise, which requires coordinated efforts from all the relevant departments in the hospital. Quality care for patients is crucial in the aspect of patient safety. A hospital safety committee reviews all the incidences of laboratory reporting including the pre- analytical, analytical and post- analytical phases.

Conclusion:

Laboratory results are required for the correct diagnoses and management of various clinical conditions without which effective therapy may not be instituted. Accurate and precise laboratory test results depend on correct flow of all the involved processes described. Errors in any of these processes, causes delay or ineffective therapy in patient care. The results of the study also show that among the laboratory processes, most errors have occurred during the pre-analytical phase.

Pre-analytical errors, (that occur before samples are analysed), causes samples to be rejected, repeat sampling, can give erroneous results if analysed, and can even result in difficulties in post analytical phase during reporting. All these cause loss of time, loss of resources, and costs, while also incurring additional work for staff and may increase risks also.

A lot of sampling errors occur due to preventable causes, and can be minimised by team work, correct guidance, prioritizing techniques, effective supervision of daily work, proper training and education of healthcare professionals.

Most rejections were from critical care areas of the hospital, which clinically require more urgent results, and therefore these delays cause a more negative impact on critical patient care.

Sampling errors also comprising patient care due to factors such as various traumas of repeat sampling, as well as possibilities of issuing erroneous results, all of which can result in unnecessary delays, unnecessary treatments or lack of needed therapy.

A quality laboratory management system needs to be established in order to properly assess, record data and retrieve them properly.

Importance has to be directed at reduction of all errors, with special consideration of pre analytical factors, for accurate and precise results for effective and safe patient care.

References

Bekele, T., Gebremariam, A., Kaso, M., & Ahmed, K. (2015). Attitude, reporting behavour and management practice of occupational needle stick and sharps injuries among hospital healthcare workers in Bale zone, Southeast Ethiopia: a crosssectional study.

Chawla, R., Goswami, V., Tayal, D., & Mallika, V. (2010). Identification of the types of preanalytical errors in the clinical chemistry laboratory. Lab Med, 41, 89-92.

Chhillar, N., Khurana, S., Agarwal, R., & Singh, N. (2011). Effect of Pre-Analytical Errors on Quality of Laboratory Medicine at a Neuropsychiatry Institute in North India. Indian J Clin Biochem, 46-49.

Dikmen, Z., Pinar, A., & Akbiyik, F. (2015). Specimen rejection in laboratory medicine: Necessary for patient safety? Biochemia Medica, 377-385.

Dr.Goswami, A., Dr.Roy, S., & Dr.Goawami, N. (2014). Evaluation of Specimen rejection rate in Hematology Laboratory. IOSR Journal of Dental and Medical Sciences (IOSR-JDMS), 01-04.

Gimenez-Marin, A., Rivas-Ruiz, F., Perez-Hidalgo, M. D., & Monila-Mendoza, P. (2014). Pre-analytical errors management in the clinical laboratory:a five-yearols study. 248-257.

Goswami, B., Singh, B., Chawla, R., Gupta, V. K., & Mallika, V. (2010). Turn Around Time 9TAT) as Benchmark of Laboratory Performance. Indian J Clin Biochem, 376-379.

Gupta, V., Negi, G., Harsh, M., Chandra, H., Agarwal, A., & Shrivastava, V. (2015). Utility of sample rejection rate as a quality indicator in developing countries. J Nat Acced Board Hosp Healthcare Providers, 2(1), 30-35.

Hawkings, R. (2012). Managing the pre and post analytical phases of the total testing process. Ann Lab Med, 32, 5-16.

Jacobsz, L., Zemlin, A., Roos, M., & Erasmus, R. (2011). Chemistry and heamatilogy sample rejection and clinical impact in a tertiary laboratory in Cape town. Clin Chem lab Med, 49(12), 2047-50.

Karcher, D. S., & Lehman, C. M. (2014). Clinical Consequences of Specimen Rejection: A College of American Pathologists Q-Probes Analysis of 78 Clinical Laboratories. Archives of Pathology &Laboratory Medicine, 1003-1008.

Kaushik, N., & Green , S. (2014, 5 18). Pre-analytical errors: their impact and how to. Retrieved 8 17, 2018, from https://www.mlo-online.com/pre-analytical-errors-their-impact-and-how-to-minimize-them.php

Kemp, G., Bird, C., & Barth, J. (2012). Short-term interventions on wards fail to reduce preanalytical errors: results of two prospective controlled trials. Annals of clinical biochemistry:International journal of laboratory medicine, 166-169.

Lillo, R., Salinas, M., Lopez-Garrigos, M., Naranjo-Santana, Y., Gutierrez, M., Marin, M., . . . Uris, J. (2012). Reducing pre-analytical laboratory sample errors through educational and technological interventions. Clin Lab, 911-7.

Nikolac, N. (2014). Lipemia: causes, interference mechanisms, detection and management. Biochem Med (Zagreb), 57-67.

Ning, H., Lin, C., Chiu, Y., Wen, C., & Peng, S. (2016). Laboratory Specimen Identification Errors following Process Interventions: A 10-Year Retrospective Observational Study. PLoS ONE, 11(8), e0160821.

Plebani, M. (2009). Exploring the iceberg of errors in laboratory medicine. Science Direct, 16-23.

Sareen, R., & Dutt, A. (2018). Role of Nursing Personnel in Laboratory Testing. Jaipur,India: Ann Nurs Primary Care.

Sharaki, O., Abouzeid, A., Hossam, N., & Elsherif, Y. (2014). Self assessment of pre,intra and post analytical errors of urine analysis in Clinical Chemistry laboratory of Alexandria Main University. Human Organ Plastination, 96-102.

Shashi, U., Sanjay, U., Bansal, R., JeelaniN, & Bharat, V. (2013). Types and Frequency of Preanalytical Errors in Haematology Lab. J Clin Diagn Res, 7(11), 2491-2493.

Stark, A., Jones, B. A., Chapman, D., Well, K., Krajenta, R., Meier, F. A., & Zarbo, R. J. (2007). Clinical Laboratory Specimen Rejection—Association With the Site of Patient Care and Patients' Characteristics: Findings From a Single Health Care Organization. Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine, 588-592.

Wadhwa, V., Rai, S., Thukral , T., & Chopra, M. (2012). Laboratory quality management system: Road to accreditation and beyond. Indian Journal of Medical microbiology , 30(2), 131-140.

Yeates, RL. (2016, September). An investigation in pre-analytical error in a medium sized pathology laboratory:frequency,origin,type and a proposed intervention. James Cook University. Retrieved from James cook university.

Comments

No comments