Compliance of WHO Surgical Safety Checklist completion in operation theatres of Tertiary Care Hospital, Maldives: Safe surgery saves life

Abstract

Background:

Research suggests that Surgical Safety Checklist (SSCL) can reduce mortality and other post-operative complications. The implementation of 19 – items Surgical Safety Checklist developed by the World Health Organization, is being enforced in operation theatres globally.Existing evidence suggests that communication failures are common in the operating room, and that they lead to increased complications, including infections

Aim/s:

The objective is to investigate the compliance of Surgical Safety checklist completion in operation theatres of tertiary care hospital in Maldives.

Method:

A retrospective study design was used to analyze three hundred and ninety-eight surgical procedures, from January 2017 till March 2018. The data was analyzed using three variables, Sign-in, Time-out and Sign- out, and the results are displayed as percentage.

Results:

Overall compliance of the SSCL completed was 67% addressing all the items of the checklist during the three phases, however 33% of the cases failed to complete either one of the items in the checklist in one of the phase over the study period. Total compliance for Sign-in phase was 74%, Time-out phase was 83% and 78% in Sign-out phase. Compliance for process indicators reveals a good patient safety outcome comparatively.

Conclusion: The study revealed inconsistencies when applying SSCL with missing documentation and incomplete items of checklist during the three phases over the period. Adaptive changes brought to the department culture of introducing SSCL may take longer time to achieve the target compliance but imparting the culture is more important for the sustainable improvements.

Key words

Safe Surgery, Quality improvement, Surgical safety Checklist, morbidity and mortality, patient safety

Introduction

Two third of the world’s population have no access to safe and affordable surgery. According to a new study in Lancet, millions of people are dying from treatable surgical interventions which could have saved their lives (Mazumdar, 2015). Millions of surgical procedures are under taken each year globally, where countries spend $100 per head on health care out of which most of it are spent on major surgical procedures in a population of 100 000 (Haynes, et al., A Surgical Safety Cheklist to reduce mobidity and mortality in a global population , 2009). WHO 19-item Safe surgery checklist aims to decrease errors and adverse events, increasing teamwork and communication in surgery whilst showing a significant reduction in both morbidity and mortality around the world (Weiser, et al., 2010 ). Patient safety remains the most important priority for this tertiary care center and patients who undergoes surgeries are assured to experience safety at all times. WHO surgical safety checklist was implemented in this tertiary care hospital in the year 2016, and the Checklist is being used in all operating rooms before commencing a surgery.

The main aim is to investigate the actual usage of the checklist and to record deviations for the purpose of identifying improvements. Like all other checklists, the surgical checklist is similar to an airline pilot's checklist used just before take-off. It is a final check prior to surgery used to make sure everyone knows the important medical information they need to know about the patient, all equipment is available and in working order, and everyone is ready to proceed. Thus, it has three vital phases to complete before commencing the surgery, where the whole team reviews the safety components in each phase. This article will include the compliance of variables based on Sign-In Phase (the briefing phase), Time-Out Phase and Sign-Out Phase (Debriefing phase). WHO SSCL has essential items in each phase to prevent patient harm and promoting patient safety. The briefings and debriefings at each stage gives time to get ready with the surgery before commencing it. Therefore, this study will mainly focus on the actual usage of checklist in accordance to the items of the checklist for its completeness.

Existing evidence suggests that communication failures are common in the operating room, and that they lead to increased complications, including infections. Use of a surgical safety checklist may prevent communication failures and reduce complications. Initial data from the World Health Organization Surgical Safety Checklist (WHO SSCL) demonstrated significant reductions in both morbidity and mortality with checklist implementation. A growing body of literature points out that while the physical act of “checking the box” may not necessarily prevent all adverse events, the checklist is a scaffold on which attitudes towards teamwork and communication can be encouraged and improved. Recent evidence reinforces the fact of compliance with the checklist is critical for the effects on patient safety to be realized (Sendlehofer, et al., 2018)

Building on this early success, the World Health Organization's Patient Safety Program ‘Safe Surgery Saves Lives’ developed a Surgical Safety Checklist as a means of improving the safety of surgical care around the world. (Forum discusses Surgical Safety Checklist initiative - New from the American college of surgeons, 2014) In a multinational study involving eight hospitals from diverse economic settings, its use improved compliance with standards of care by 65% and reduced the death rate following surgery by nearly 50% (WHO, 2008)

The Checklist divides the operation into three phases where the period before induction of anesthesia is Sign In phase, the period after induction and before surgical incision is the Time Out phase, and the period during or immediately after wound closure but before removing the patient from the operating room is the Sign Out phase. In each phase, the Checklist coordinator must be permitted to confirm that the team has completed its tasks before it proceeds with the procedure further (WHO, 2008).

Literature review

Surgical care volumes yearly and it is performed in wealthy and poor, rural and urban and in all regions. In the year 2002, the world bank reported, an estimated value of 164 million disabilities –adjusted life years where 11% of the cases were surgically treatable. Studies have shown that industrialized countries death of perioperative surgery rates of 0.4 to 0.8 of major complication of 3 to 17% (Haynes, et al., A Surgical Safety Cheklist to reduce mobidity and mortality in a global population , 2009).

Out of 122 countries, 3865 hospitals have registered as safe surgery saves lives campaign to implement the WHO Surgical Safety Checklist at a national level. The checklist was implemented and introduced in all theatres with data collection and monitoring which includes compliance rate of checklist, complications and mortality rates. (Weiser, et al., 2010 ) In May 2009, New Zealand Hospital in Naevstved, Denmark, during the first four months of Surgical safety checklist use, it was found that they had a 35% reduction in mortality rate (World Health Organisation , 2010)

Insufficient instruction prior to implementation of the checklist is a barrier for proper implementation of SSCL with poor team culture as a result. (Sendlehofer, et al., 2018). An increased compliance is observed in Wales Hospitals at a national scale, with appropriate timing of antibiosis administration and verification of patient’s name, procedure and on site marking. (World Health Organisation , 2010)nevertheless, a checklist need to applied properly as intended which could be either evaluated using a quantitative approach or through a qualitative approach such as using the method of direct observations (Sendlehofer, et al., 2018)

Although surgical procedures are meant to save lives, unsafe surgical practices would subsequently lead to harm patients. Thus the significant implications may include; the reported crude mortality rate after major surgeries was 0.5 – 5%, complication after inpatient operations occur in up to 25% of patients, in industrialized countries, nearly half of all adverse events in hospitalized patients are related to surgical care at least half of the cases in which surgery led to harm are considered to be preventable, mortality from general anesthesia alone is reported to be as high as one in 150 in some parts of sub-Saharan Africa.

Surgical care has been an essential component of health care worldwide for over a century. As the incidences of traumatic injuries, cancers and cardiovascular disease continue to rise, the impact of surgical intervention on public health systems will continue to grow.

surgery is often the only therapy that can alleviate disabilities and reduce the risk of death from common conditions. Every year, many millions of people undergo surgical treatment, and surgical interventions account for an estimated 13% of the world’s total disability-adjusted life years (DALYs).

WHO has undertaken a number of global and regional initiatives to address surgical safety. Much of this work has stemmed from the WHO Second Global Patient Safety Challenge “Safe Surgery Saves Lives”. Safe Surgery Saves Lives set about to improve the safety of surgical care around the world by deï¬ning a core set of safety standards that could be applied in all WHO Member States (WHO, n.d.)

Furthermore, many countries are still continuing to make partnership with Safe surgery, so as to discuss the success and challenges of implementing the Surgical Safety Checklist in 100 percent of theatres in all the states (Forum discusses Surgical Safety Checklist initiative - New from the American college of surgeons, 2014). A study done in Swedish Country Hospital for the compliance of WHO Surgical Safety Checklist reveals that Time-out is not always applied as intended. The questions with the best compliance on the checklist was for patient Identification, ‘planned operation’, ‘anticipated critical events’: ‘surgeons review’, ‘antibiotic prophylaxis’ are all concerned with avoiding direct harm to the patient which would avoid active failures. Compliance with the WHO Surgical Safety Checklist: deviations and possible outcomes(Rydenfalt, Johansson, odenrick, AkermanPer, & Larsson, 2013 ).

The compliance was overlooked in some studies for particularly communication, and reveals most of the briefings happens 92% for all phases, only Sign-in -34% , Time-out as 47% which is due to incompleteness of documentation (Lingard , et al., 2008).

THODOLOGY

A retrospective study design was used to analyze three hundred and ninety-eight surgical procedures from January 2017 till March 2018 in a 100 bed tertiary care hospital in the capital city of Maldives. SSCL usage was audited within this period and this data is being used to investigate the compliance rate of surgical procedures in operation theatres, thus a retrospective study design was selected.

The study was approved by the Ethical committee of ADK Hospital, as it’s a checklist used in hospital a consent form is not applicable to use, as a patient is not involved in the study

All the surgical cases were selected randomly and observed for their Surgical Safety Checklist callout which includes the three phases of debriefings. The circulating nurse was designated as a checklist coordinator in all the cases and was obliged to call out and only tick the checkbox if an answer was given to the corresponding question.

Prior to the first attempt to use the checklist in the operation room, the corresponding operating teams were given introduction and training with practical demonstration. Auditors were trained to collect data using a Quantitative audit tool. New staffs had been introduced to the checklist in the induction program when they join.

A quantitative audit tool was used to measure the compliance of SSCL in the theatres randomly, for the completeness of the checklist. The major components covered in the tool were, clear announcement of the checklist, team respond appropriately, silent cockpit observed, any distractions or disruptions, documentation completed accurately, documentation completed at each stage of the process. For each item a key from 1 to 5 was given, where key 1 is for lack of staff, key2 for late arrival, key3 for equipment issues, key 4 for lack of respect for hospital policy and key 5 for others. In addition to this six process indicator were used to check further process flow of patient safety.Process indicators includes; oral confirmation of patient identity, objective airway evaluation, pulse oximeter used, two peripheral or one IV catheter present at the time of incision, sponge count completed, all six safety indicators performed. A complete checklist is defined as a checklist in which all items have been ticked. Checklists were kept as part of each patient’s medical record. Monthly audits were taken randomly by an auditor upon their observations.

Three hundred and ninety-eight surgical procedures were analyzed using the audit tool for its compliance at each phase using three variables, Sign-in, Time-out and Sign- out. The results are displayed as percentage according to the above mentioned components. Each audit form was checked using the above mentioned components of the audit, thus if any phase of SSCL is not performed according to the components of the tool, it was considered as not done.

Compliance was calculated by the number of times all three phases of the surgical safety checklist were completed. The surgical safety checklist is considered as "performed" when the surgical team members have implemented and/or addressed all of the necessary tasks and items in each of the three phases: Briefing; Time Out; and debriefing. Target compliance is to achieve 90% above for all the cases by doing all the three phases completing all the items in the checklist.

RESULT

The results show that the WHO Surgical Safety Checklist is not always applied as intended. During the study period, a total of three thousand seven hundred and ninety-eight cases were performed out of which three hundred and ninety-eightcases were audited.

The percent compliance is calculated as follows:

# of times all three phases of the surgical safety checklist was performed

_________________________________________________________ x 100 = % compliance

Total surgeries

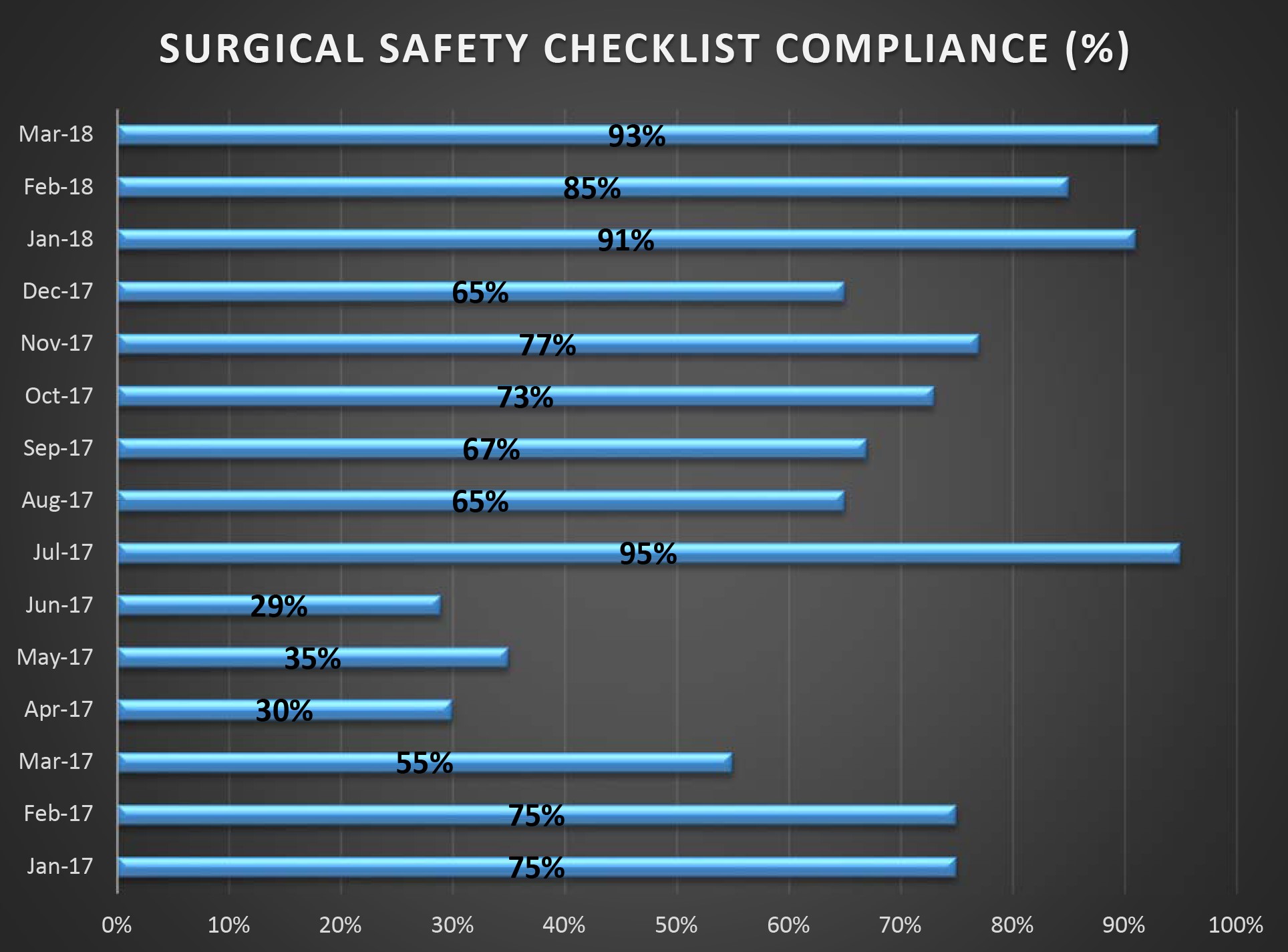

COMPLIANCE OF SURGICAL SAFETY CHECKLIST FROM JAN 2017 -MARCH 2018

Fig 1

.jpg)

As an overall compliance of completed checklist was 67% with all items addressed in all phases where else 33% of the cases failed to complete the checklist in one of the phase.

Fig 2

Fig 2 shows the total compliance for each month from Jan 2017 – March 2018

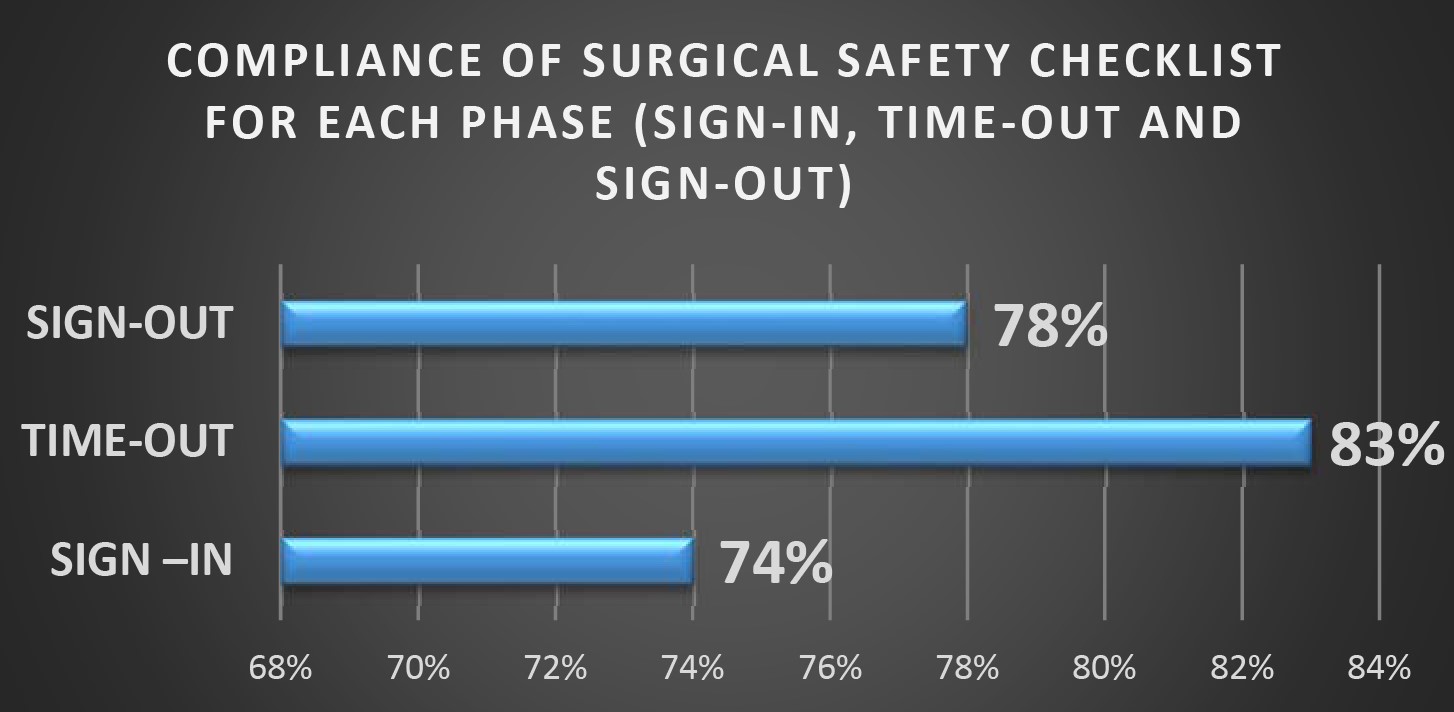

Fig3

Another area observed within the period was the total compliance of each phase, as apparent from the bar chart, sign in phase has achieved 74%, while Time-out phase and Sign-out phase has achieved 83% and 78% respectively.

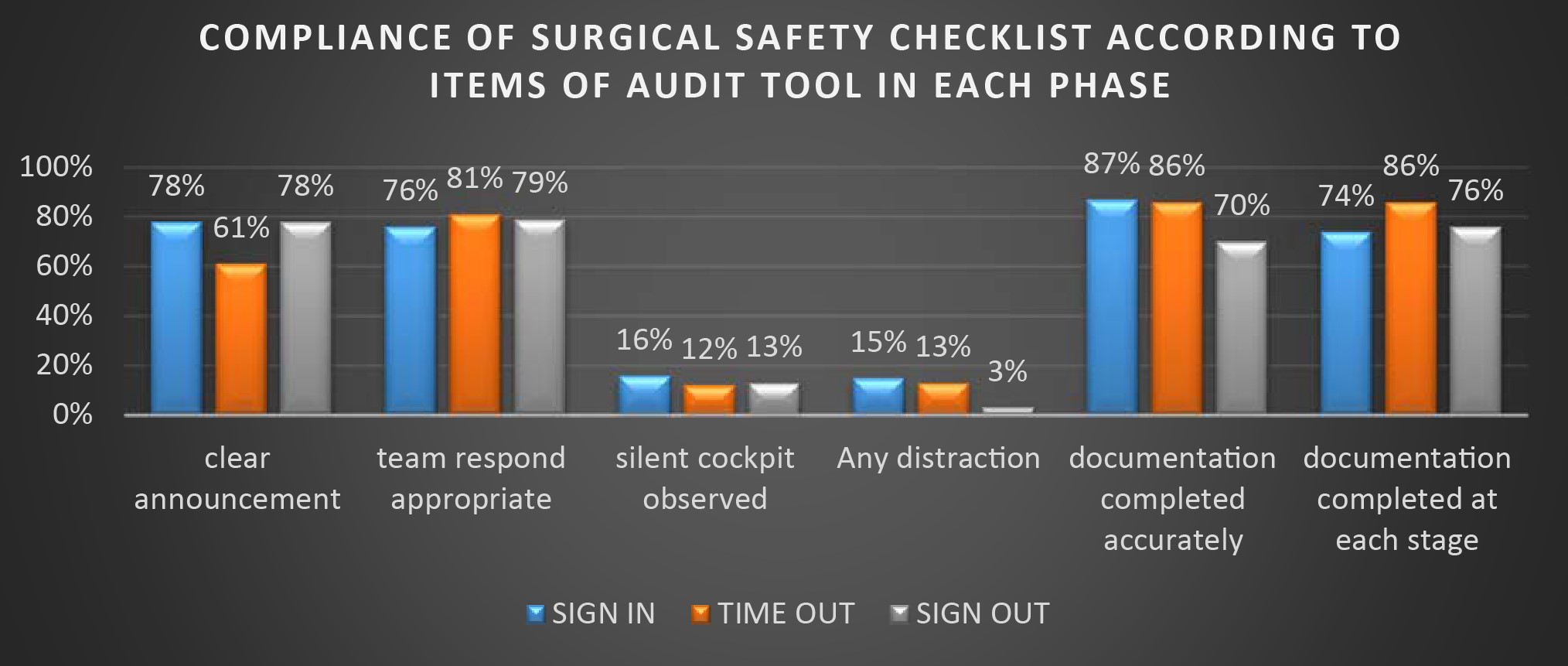

COMPLIANCE OF SURGICAL SAFETY CHECKLIST ACCORDING TO ITEMS OF AUDIT TOOL IN EACH PHASE

Fig4

As apparent, total compliance for clear announcement made in Sign-in phase is 78%, team respond is 76%, silent cockpit observed during the phase was 16%, distractions was 15%, documentation completed accurately was 87% and documentation completed at each stage was 74%. Total compliance for time-out phase was, for clear announcement made 61%, team respond appropriately was 81%, silent cockpit observed during the phase is 12%, distractions 13%, documentation completed accurately was 86% and documentation completed at each stage was also 86%. Sign-in phase, clear announcement made 78%, team respond appropriately was 79%, silent cockpit observed during the phase is 13%, distractions 3%, documentation completed accurately was 70% and documentation completed at each stage was 76%

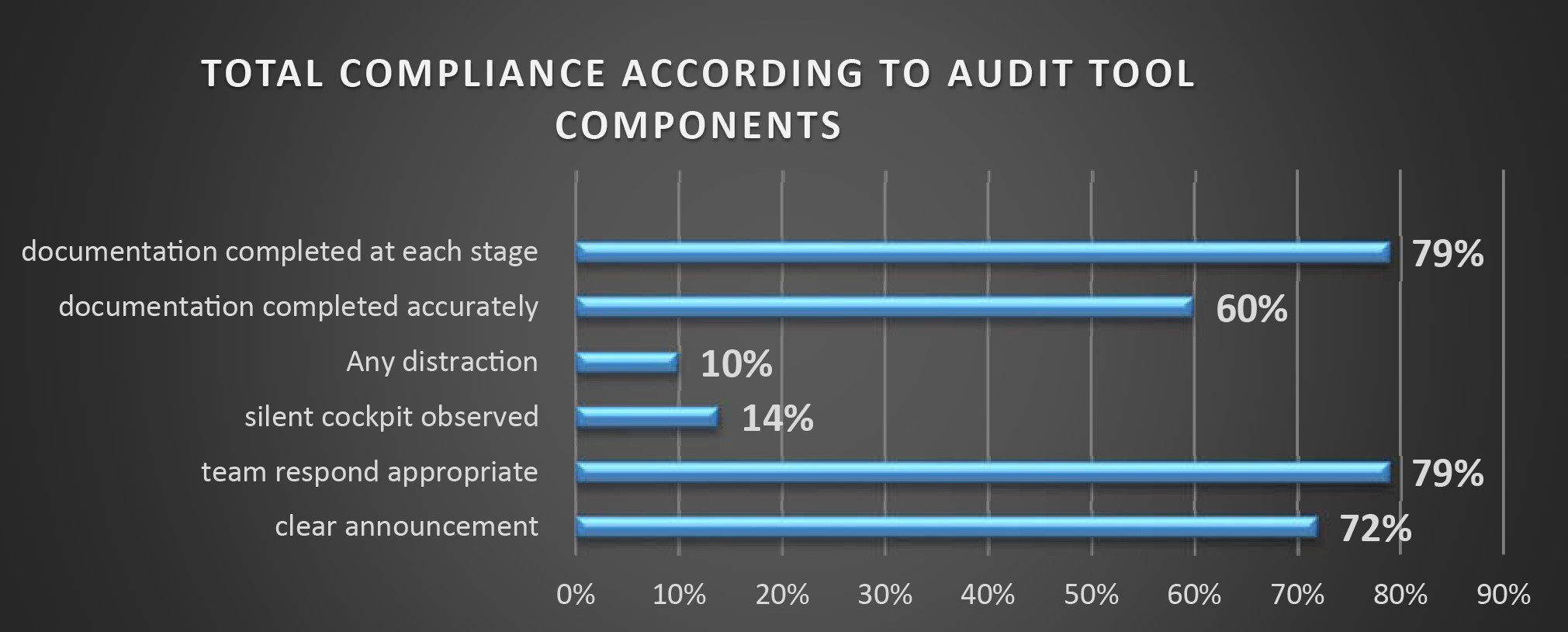

Fig5

Fig 5 shows audit tool items over all compliance over the period.

TABLE1

EXPLANATORY NOTES:

|

ISSUE |

Required behavior/observations |

|

Clear announcement of safety checklist? |

A designated member of the team leads the team through the appropriate stages of the safety checklist. The team member is observed to use the check list and to clearly let the team know that the safety check is taking place |

|

Team respond appropriately |

On announcement of the start of the safety check- the team focus on the questions being asked. Any potential distractions such as phone calls, are eliminated. No disrespectful comments are made about the process. |

|

Checklist is read out accurately |

A distraction or interruption can be people chatting, using mobile phone, not focusing on the checklist, or people entering the theatre at the time of the check. If staff enter the theater but do not disturb the team undertaking the check, this is not classified as an interruption. |

|

Documentation observed to be completed at the time of undertaking the check |

The observer should ensure all documentation is completed during the check. All documentation is required to be complete BEFORE the patient leaves the theatre and should not be completed retrospectively. |

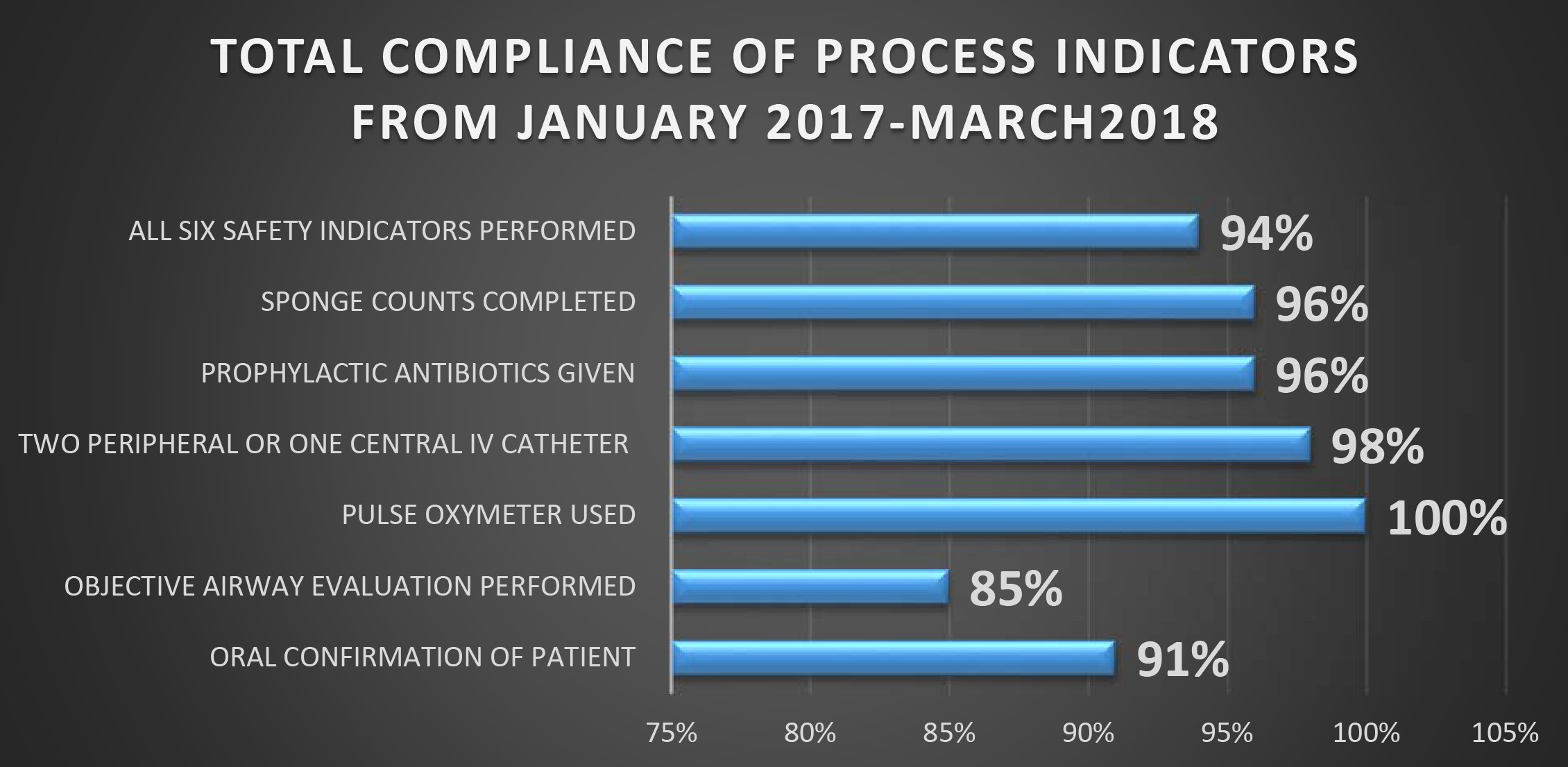

Fig6

Total compliance of process indicators shows, for oral confirmation of the patient 91%, objective airway evaluation performed was 85%, pulse oximeter used in 100% of the case, 98% for two peripheral or one central IV catheters used, 96% shows usage of prophylactic antibiotics, sponge counts completed as 96% % and 94% of the cases have achieved all six safety indicators performed.

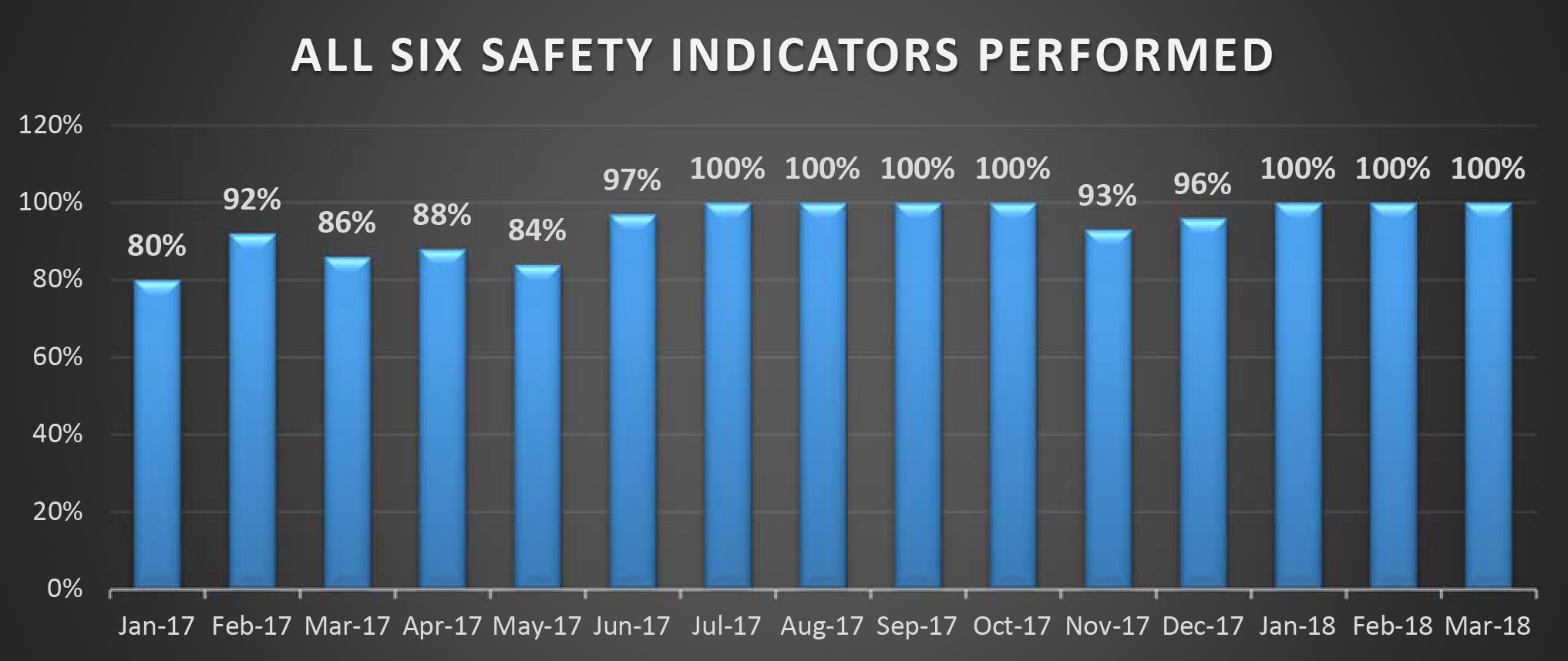

Fig7

Safety indicators reveals that there was a vast improvement in checking the safety of the patients using the indicators. Safety indicators include all items mentioned in Fig 6.

DISCUSSION

Study components

In spite of the usage of SSCL, studies has shown that although SSCL compliance is documented as 100% compliance in reality the proper usage of checklist for its completion is less than 10% of the time in theatres (Gillepsie , et al., 2018 ). The implementation of WHO Surgical Safety Checklist is to improve the surgical care and patient safety in theatres. However, its introduction and sustainability is always a big challenge, but it’s important to investigate actual usage of checklist for its competition and its information is crucial from an organizational perspective, to identify possible improvements (Melekie & Getahun, 2015). Thus, the study assessed the frequency of deviations and factors that may have contributed to deviations. A study conducted in a Swedish country hospital reveals that total compliance of performing SSCL was 96% out which 54% was achieved for the completeness of the items in the SSCL (Rydenfalt, Johansson, odenrick, AkermanPer, & Larsson, 2013 ).

Although the hospital reported 100 % utilization of the checklist in the theatres, the baseline of checklist completeness is only 67% in accordance with the items of the checklist during the three phases. 32% of the cases checklist was used but not all items were completed and some of the cases missed either one or two of the phases. Study done in operation theatres of Swedish country hospital reveals that 54% of the cases completed the checklist out of 24 surgical procedures recorded (Rydenfalt, Johansson, odenrick, AkermanPer, & Larsson, 2013 ) . From a safety perspective, the checklist can be regarded as a barrier or a ‘defense’ against failure (Haynes, et al., A Surgical Safety Checklist to reduce Morbiduty and Mortality in a global population , 2009).

Not all the phases were addressed according to the items in checklist.As apparent in the bar chart, Time-out phase has the highest compliance rate compared to other two phases and the lowest compliance for Sign-in phase, where each phase of the SSCL plays equal important role with regard to patient safety. Achieving 74% Sign-in phase, omitting important components within the phase like patient identification and allergies etc are risky. Likewise, for Time-out phase 83% before commencing a surgery is still risky to proceed leaving behind some of the critical items within the phase where critical events are put forward to address including prophylaxis antibiotic administration and estimated blood loss which would further keep necessary perfusions ready for the surgery (Melekie & Getahun, 2015). Sign-out achieving 78%, again gives an alarm for the very essential components within the phase to address, where confirmation of the procedure being performed, equipment issues to address and most importantly the key recovery management of the patient are discussed within this phase. Thus for all these items in the checklist prevents and promotes patient safety ahead of a surgery and gives time for briefings and debriefings before and after a surgery. In contrast, compared to another study which was done in Northwest of Ethopia, shows that out of 282 operations performed the checklist were used in 39.7% of the cases and Sign-in, Time-out and Sign-out were missed in 30.5% of the cases. Result reveals that main reason for low compliance as lack of trainings and lack of corporation among surgical team members (Melekie & Getahun, 2015).

Most of all the items in each phase plays an important role in preventing the most common errors that causes serious harm to the patient. According to WHO implementation manual the checklist ensures the teams consistently in following critical safety steps and thereby minimizing the most common and avoidable risks endangering the lives and well-being of surgical patients (WHO, 2008). When we look at each item in the checklist in comparison to each phase, it shows that Sign-in phase, Time-out phase and Sign-out phase has not reached to the target compliance of clear announcement being made. It gives a percentage of 78%, 61% and 78% respectively. It is crucial to have a 100% clear announcement made during each phase and specially Time-out phase, where it leaves a question behind, whether all the members heard the SSCL call out.

Secondly when looking at the team response it has scored, 76%, 81% and 79% in each phase respectively. Team response is another area where it has scored low in all the phases, most of all in Sign-in, where patient identification and allergies are directly asked to the patient before induction of anesthesia, where in Time-out the whole team confirms the patient identification once again and the surgery site and side, blood loss and etc. Thus team’s response in this phase was 81% where its again equally important in Sign-out phase for the procedure confirmation and key recovery management. In the audit tool silent cockpit refers to a member of the team where a question is being asked but not responded to the question. Silent cockpit is also observed in all the phases, surprisingly the result in each phase is high comparatively.

The next item is if there are any distractions during the checklist call out in each phases, a distraction or interruption can be people chatting, using mobile phone, not focusing on the checklist, or people entering the theatre at the time of the check. If staff enter the theater but do not disturb the team undertaking the check, this is not classified as an interruption. Distractions during Sign-in phase has a total compliance of 15%, Time-out has 13% and 3% distractions in Sign-out phase.

When we look into the accuracy of documentation, where observer ensure that all documentation is completed during the check and it is required to be completed before the patient leaves the theatre and should not be completed retrospectively. Thus for this a total compliance was, for Sign-in was 87%, Time-out was 86% and Sign-out giving the lowest of all was 70% of completed documentation. Likewise, for documentation completed at each stage was also calculated where Sign-in phase it was 74%, Timeout phase it was 86% and 76% for Sign-Out phase. A study conducted in university hospital of Austria reveals that SSCL was used incomplete and merely as a tick off exercise for monitoring purpose which hinders the actual process of usage in theatres and noticeably decline in clinical improvements (Sendlehofer, et al., 2018)

Compliance for process indicators reveals a good patient safety outcome comparatively in all the phases which is above the target compliance accept for obtaining an evaluation of airway which scored 85%. An airway evaluation should be performed before commencing any surgery. Although 91% of oral confirmation of the patient was achieved, this is an area where 100% should be achieved in all three phases for the very first basics of patient safety, but this shows that most of the time patient identification is being followed in each phase. Usage of pulse oximeter was 100%, which shows that the patient is being monitored in each case, the other very important item is having two peripheral or one central IV catheter, where the compliance was 98%, having at least one IV catheter for each case would save a lot of time in saving the patient who need to be perfused immediately. Another major item was completion of sponge counts, where its showed 96% of compliance, however when we look into patient safety aspect 4% chance is there for leaving an instrument or a sponge inside the patient’s body causing a harm to the patient. Overall compliance for all six safety indicators performed was 94%, leaving 6% for unsafe practice which would lead to an error. A study done in university hospital in Queensland Australia, shows that behavioral deficits and contextual factors during observations, described in earlier work and most common reasons health professionals identified for non-compliance were forgetfulness in using the SSCL or in addressing some of its elements, or a lack of time to complete it (Gillepsie , et al., 2018 ).

CONCLUSION

Although there is a vast amount of data which suggests for a proper implementation of SSCL, it is important to know how to implement the checklist most effectively. Result indicates that there is potential for improvement, from an organizational perspective this result can be used to identify possible improvements in items of the checklist for each phase. In order to improve the completeness of checklist, it is important to know staff attitude towards checklist items which may need to be changed. Thus, it is important to find staff perception towards SSCL and barriers of completing the items of checklist. It is important to conduct a study on this area using a snapshot audit which would be more valuable tool to use for an observational study like this which would give an insight than a mere completeness of ticks in SSCL documents. Adaptive changes brought to the department culture of introducing SSCL may take longer time to achieve the target compliance but imparting the culture is more important for the sustainable improvements. Sustaining and building the culture of safety is important for health care members who plays a vital role in patient safety. Such checklists are barriers to overcome the obstacles before commencing surgeries.

References

(2014). Forum discusses Surgical Safety Checklist initiative - New from the American college of surgeons. Chicago.

Gillepsie , B., Hardbeck, E., Lavin , j., hamilton, K., Gardiner, T., Withers , t., & Marshall, A. (2018 ). Evaluation of a patient safety program on Surgical Safety Checklist compliance : a propective longitudinal study . BMJ open quality .

Haynes, A., Weiser , T., Berry , W., Lipsitz , S., Breizat, A., Lapitan , M. C., . . . Gawande, A. (2009). A Surgical Safety Checklist to reduce Morbiduty and Mortality in a global population . The New England Journal of Medicine .

Haynes, A., Weiser, T., Berry , W., Lipsitz, S., Breizat , A.-H., Delllinger , E., . . . Moorthy , K. (2009). A Surgical Safety Cheklist to reduce mobidity and mortality in a global population . The New England Journal of Medicine.

Lingard , L., Regehr, G., Orser , B., Reznick, R., Backer , R., Doran , D., . . . Whtye , S. (2008). Evaluation of a preoperative Checklist and team briefing among surgoeans, nurses and anaestheologists to reduce failures in communication . JAMA Surgery .

Mazumdar, t. (2015). Five billion people "have no access to safe surgery".

Melekie , T., & Getahun, G. (2015). Compliance with Surgical Safety Checklist completion in the operating room of University of Gondar Hospital, Northwest Ethopia . BMC Research Notes .

Rydenfalt, C., Johansson, G., odenrick, P., AkermanPer, k., & Larsson, A. (2013 ). Compliance with the WHO Surgical Safety Checklist: deviation and possible improvements . International Journal for Quuality in health care , 182-187.

Sendlehofer, G., Lumenta , D. B., Pregartner, G., Leitgeb, K., Teifenbacher , P., gombotoz , V., . . . Brunner , G. (2018). Reality check of using the surgical safety checklist: A qualitative study to observe application errors during snap shot audits. PLoS ONE , 13(9).

Weiser , T. G., Regenbogen, S. E., Thompson , K. D., Haynes , A. B., Lipstiz, S. R., Berry , W. R., & Gawande , A. A. (2008). An Estimataion of the global volume of surgery : a modelling strategy based on available data . The Lancet .

Weiser, T. G., Haynes, A. B., Lashoher, A., DziekanDaniel J, g. B., Berry , W. R., & Gawande , A. A. (2010 ). Perspectives in quality: designing the WHO Surgical Safety Checklist . International Journal for Quality in Health Care , 365-370.

WHO. (n.d.). Retrieved from Patient Safety : http://www.who.int/patientsafety/safesurgery/en/

WHO. (2008). Retrieved from IMPLEMENTATION MANUAL – WHO SURGICAL SAFETY CHECKLIST (FIRST EDITION): http://www.who.int/patientsafety/safesurgery/tools_resources/SSSL_Manual_finalJun08.pdf

World Health Organisation . (2010). Retrieved from Safe Surgery Saves lives Newsletter : http://www.who.int/patientsafety/safesurgery/sssl_newsletter_aug_2010.pdf

Comments

No comments